Scientific journal writing has a problem:

- It’s the major way scientists communicate their findings to the world, in some ways making it the carrier of humanity’s entire accumulated knowledge and understanding of the universe.

- It’s terrible.

This has two factors: Accessibility and approachability. Scientific literature isn’t easy to find, and much of it is locked behind paywalls. Also, most scientific writing is dense, dull, and nigh-incomprehensible if you’re not already an expert. It’s like those authors who write beautiful works of literature and poetry, and then keep it under their bed until they die – only the poetry could literally be used to save lives. There are systematic issues with the way we deal with scientific literature, but in the mean time, there are also some techniques that make it easier to deal with.

This first post in this series will discuss accessibility: how to find papers that will answer a particular question or help you explore a subject.

The second post in this series discusses approachability: how to read a standard scientific journal article.

How to Find Articles

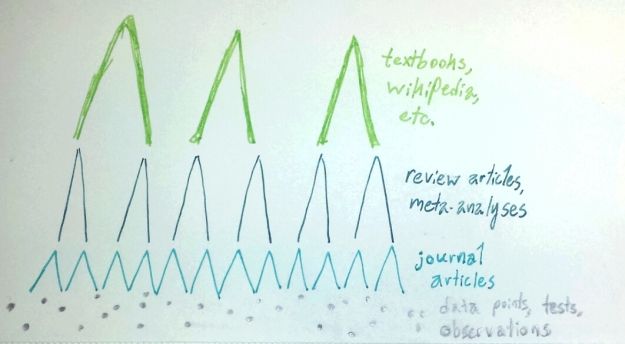

Most scientific papers come from a small group of researchers who do a series of experiments on a common theme or premise, then write about what they learned. If your goal is to learn more about a broad subject, ask yourself if a paper is actually what you want. Lots of quality, scientifically rigorous information can be obtained in other ways – textbooks, classes, summaries, Wikipedia, science journalism.

The great food web of “where does scientific knowledge come from anyways?”

When might you want to turn to the primary literature? If you’re looking at very new research, if you’re looking at a contentious topic, if you’re trying to find a specific number or fact that just isn’t coming up anywhere else, if you’re trying to fact-check some science journalism, or if you’re already familiar enough with the field that you know what’s on Wikipedia already.

You can look at the citations of a journal article you already like. Or, find who the experts in a field are (maybe by looking at leaders of professional organizations or Wikipedia) and read what they’ve written. Most science journalism is also reporting on a single new study, which should be linked in the article’s text.

If you have access to a university library, ask them about tools to search databases of journal articles. Universities subscribe to many reliable journals and get their articles for free. Your public library may also have some.

Google Scholar is a search engine for academic writing. It has both recent and very old papers, and a variety of search tools. It pulls both reliable and less reliable sources, and both full-text and abstract-only articles (IE, articles where the rest is behind a paywall.) Clicking “All # Versions” at the bottom of each result will often lead you to a PDF of the full text.

If you’ve found the perfect paper but it’s behind a paywall- well, welcome to academia. Don’t give up. First up, put the full name of the article, in quotes, into Google. Click on the results, especially on PDFs. It’ll often just be floating around, in full, on a different site.

If that doesn’t work, and you don’t have access through a library, well… Most journals will ask you to pay them a one-time fee to read a single article without subscribing. It’s often ridiculous, like forty dollars. (Show of hands, has anyone reading this ever actually paid this?)

But this is the modern age, and there are other options. “Isn’t that illegal?” you may ask. Well, yes. Don’t do illegal things. However, journals follow two models:

- Open content access, researchers pay to submit articles

- Content behind paywalls, researchers can submit articles for free

As you can see, fees associated with journals don’t actually go to researchers in either model. There are probably some reasonable ethical objections to downloading paywalled-articles for free, but there are also very reasonable ethical objections to putting research behind paywalls in general.

How good is my source?

Surprise! There’s good science and bad science. This is a thorny issue that might be beyond my scope to cover in a single blog post, and certainly beyond my capacity to speak to every field on. I can’t just leave you here without a road map, so here are some guidelines. You’ll probably have two goals: avoiding complete bullshit and finding significant results.

Tips for avoiding complete bullshit

- Some journals are more reliable than others. Science and Nature are the behemoths of science and biology (respectively), and have extremely high standards for content submission. There are also other well-known journals in each field.

- Well-known journals are unlikely to publish complete bullshit. (Unless they’re well known for being pseudoscience journals.)

- You can check a journal’s impact score, or how well-cited their work tends to be, which is sort of a metric for how robust and interesting the papers they publish are. This is a weird ouroboros: researchers want to submit to journals with high impact scores, and journals want to attract articles that are likely to be cited more often – so it’s not a perfect metric. If a journal has no impact score at all, proceed with extreme caution.

- Watch out for predatory journals and publishers. Avoid these like the plague, since they will publish anything that gets sent to them. (What is a predatory journal?)

- Make sure the journal hasn’t issued a retraction for the study you’re reading.

Once you’ve distinguished “complete bullshit” from “actual data”, you have to distinguish “significant data” from “misleading data” or “fluke data”. Finding significant results is much tougher than ruling out total bullshit – scientists themselves aren’t always great at it – and varies depending on the field.

Tips for finding significant results

- Large sample sizes are better than small sample sizes. (IE, a lot of data was gathered.)

- If the result appears in a top-level journal, or other scientists are praising it, it’s more likely to be a real finding.

- Or if it’s been replicated by other researchers. Theoretically, all research is expected to replicate. In practice, it sometimes doesn’t, and I have no idea how to check if a study has been replicated.

- If a result runs counter to common understanding, is extremely surprising, and is very new, proceed with caution before accepting the study’s conclusions as truth.

- Apply some common sense. Can you think of some other factor that would explain the results, that the authors didn’t mention? Did the experiment run for a long enough amount of time? Could the causation implied in the paper run other ways (EG, if a paper claims that anxiety causes low grades: could it also be that low grades cause anxiety, or that the same thing causes both anxiety and low grades?), and did the paper make any attempt to distinguish this? Is anything missing?

- Learn statistics.

If you’re examining an article on a controversial topic, familiarize yourself with the current scientific consensus and why scientists think that, then go in with a skeptical eye and an open mind. If your paper gets an opposite result from what most similar studies say, try to find what they did differently.

Scott Alexander writes some fantastic articles on how scientists misuse statistics. Here are two: The Control Group is Out of Control, and Two Dark Side Statistical Papers. These are recommended reading, especially if your subject is contentious, and uses lots of statistics to make its point.

Review articles and why they’re great

The review article (including literature reviews, meta-analyses, and more) is the summary of a bunch of papers around a single subject. They’re written by scientists, for scientists, and published in scientific journals, but they’ll cover a subject in broader strokes. If you want to read about something in more detail than Wikipedia, but broader than a journal article – like known links between mental illness and gut bacteria – review articles are a goldmine. Authors sometimes also use review articles to link together their own ideas or concepts, and these are often quite interesting.

If an article looks like a normal paper, and it came from a journal, but it doesn’t follow the normal abstract-introduction-methods-discussion-conclusion format, and subject headings are descriptive rather than outlining parts of an experiment, it might be a review article. (Sometimes they’re clearly labelled, sometimes not.) You can read these the same way you’d read a book chapter – front to back – or search anywhere in it for whatever you need.

What if you can’t find review articles about what you want, or you need more specificity? In that case, buckle up. It’s time to learn how to read an article.

> Show of hands, has anyone reading this ever actually paid this?

Haha ^_^ I have not. I would probably pay if the cost were ~$1, or if I could buy a yearly pass to all journal articles for a few hundred dollars. I would guess that publishers could sell more than 40 times more papers if they lowered the price by 40 times, but maybe they need to keep it high for other reasons.

LikeLike

> Show of hands, has anyone reading this ever actually paid this?

I did when working for GiveWell.

LikeLike

Pingback: Science for Non-Scientists | eve reviews