[Header: Illustration of meal in 1500s Mexico from the Florentine Codex.]

People began cooking our food maybe two million years ago and have not stopped since. Cooking is almost a cultural universal. Bits of raw fruit or leaves or flesh are a rare occasional treat or garnish – we prefer our meals transformed. There are other millennia-old procedures we do to make raw ingredients into cooking: separating parts, drying, soaking, slicing, grinding, freezing, fermenting. We do all of this for good reason: Cooking makes food more calorically efficient and less dangerous. Other techniques contribute to this, or help preserve food over time. Also, it tastes good.

Cuisine and Empire by Rachel Laudan is an overview of human history by major cuisines – the kind of things people cooked and ate. It is not trying to be a history of cultures, agriculture, or nutrition, although it touches on all of these things incidentally, as well as some histories of things you might not expect, like identity and technology and philosophy.

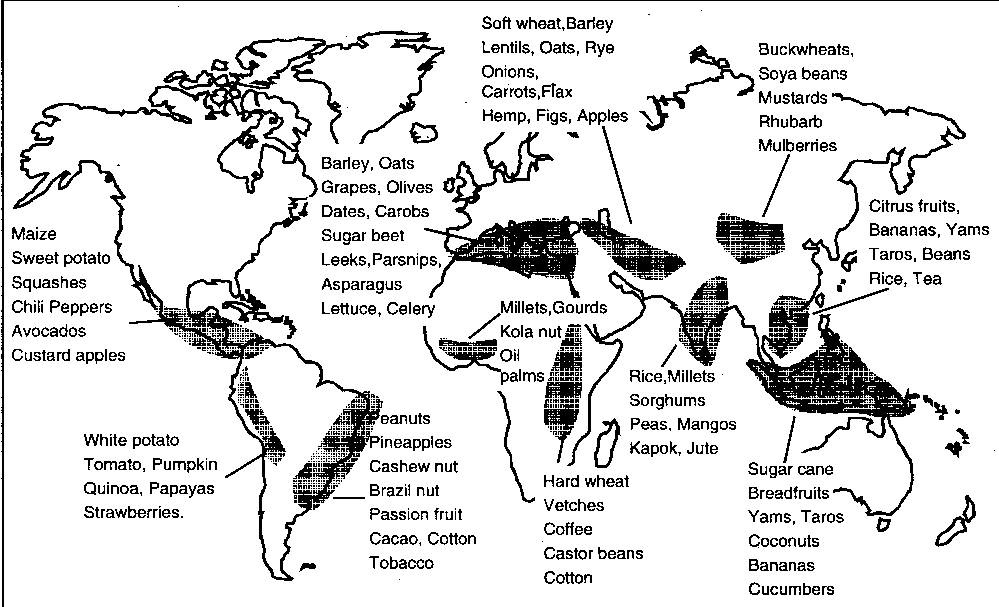

Grains (plant seeds) and roots were the staples of most cuisines. They’re relatively calorically dense, storeable, and grow within a season.

- Remote islands really had to make do with whatever early colonists brought with them. Not only did pre-Columbian Hawaii not have metal, they didn’t have clay to make pots with! They cooked stuff in pits.

Running in the background throughout a lot of this is the clock of domestication – with enough time and enough breeding you can make some really naturally-digestible varieties out of something you’d initially have to process to within an inch of its life. It takes time, quantity, and ideally knowledge and the ability to experiment with different strains to get better breeds.

Potatoes came out of the Andes and were eaten alongside quinoa. Early potato cuisines didn’t seem to eat a lot of whole or cut-up potatoes – they processed the shit out of them, chopping, drying or freeze-drying them, soaking them, reconstituting them. They had to do a lot of these because the potatoes weren’t as consumer-friendly as modern breeds – less digestible composition, more phytotoxins, etc.

As cities and societies caught on, so did wealth. Wealthy people all around the world started making “high cuisines” of highly-processed, calorically dense, tasty, rare, and fancifully prepared ingredients. Meat and oil and sweeteners and spices and alcohol and sauces. Palace cooks came together and developed elaborate philosophical and nutritional theories to declare what was good to eat.

Things people nigh-universally like to eat:

- Salt

- Fat

- Sugar

- Starch

- Sauces

- Finely-ground or processed things

- A variety of flavors, textures, options, etc

- Meat

- Drugs

- Alcohol

- Stimulants (chocolate, caffeine, tea, etc)

- Things they believe are healthy

- Things they believe are high-class

- Pure or uncontaminated things (both morally and from, like, lead)

All people like these things, and low cuisines were not devoid of joy, but these properties showed up way more in high cuisines than low cuisines. Low cuisines tended to be a lot of grain or tubers and bits of whatever cooked or pickled vegetables or meat (often wild-caught, like fish or game) could be scrounged up.

In the classic way that oppressive social structures become self-reinforcing, rich people generally thought that rich people were better-off eating this kind of diet – carefully balanced – whereas it wasn’t just necessary, it was good for the poor to eat meager, boring foods. They were physically built for that. Eating a wealthy diet would harm them.

In lots of early civilizations, food and sacrifice of food was an important part of religion. Gods were attracted by offered meals or meat and good smells, and blessed harvests. There were gods of bread and corn and rice.

One thing I appreciate about this book is that it doesn’t just care about the intricate high cuisines, even if they were doing the most cooking, the most philosophizing about cooking, and the most recordkeeping. Laudan does her best to pay at least as much attention to what the 90+% of regular people were eating all of the time.

Here’s a great passage on feasts in Ancient Greece, at the Temple of Zeus in Olympia, at the start of each Olympic games (~400 BCE):

On the altar, ash from years of sacrifice, held together with water from the nearby River Alpheus, towered twenty feet into the air. One by one, a hundred oxen, draped with garlands, raised especially for the event and without marks of the plow, were led to the altar. The priest washed his hands in clear water in special metal vessels, poured out libations of wide, and sprinkled the animals with cold water or with grain to make them shake their heads as if consenting to their death. The onlookers raised their right arms to the altar. Than the priest stunned the lead ox with a blow to the base to the neck, thrust in the knife, and let the blood spill into a bowl held by a second priest. The killing would have gone on all day, even if each act took only five minutes.

Assistants dragged each felled ox to one side to be skinned and butchered. For the assembled crowd, cooks began grilling strips of beef, boiling bones in cauldron, baking barley bannocks, and stacking up amphorae of wine. For the sacrifice, fat and leg and thigh bones rich in life-giving marrow were thrown on a fire of fragrant poplar branches, and the entrails were grilled. Symbolizing union, two or three priests bit together into each length of intestines. The bones whitened and crumbled; the fragrant smoke rose to the god.

Ancient Greek farmers had thin soil and couldn’t do much in the way of deliberate irrigation, so their food supply was more unpredictable than other places.

Country people kept a three-year supply of grain to protect against harvest failure and a four-year supply of oil.

That’s so much!

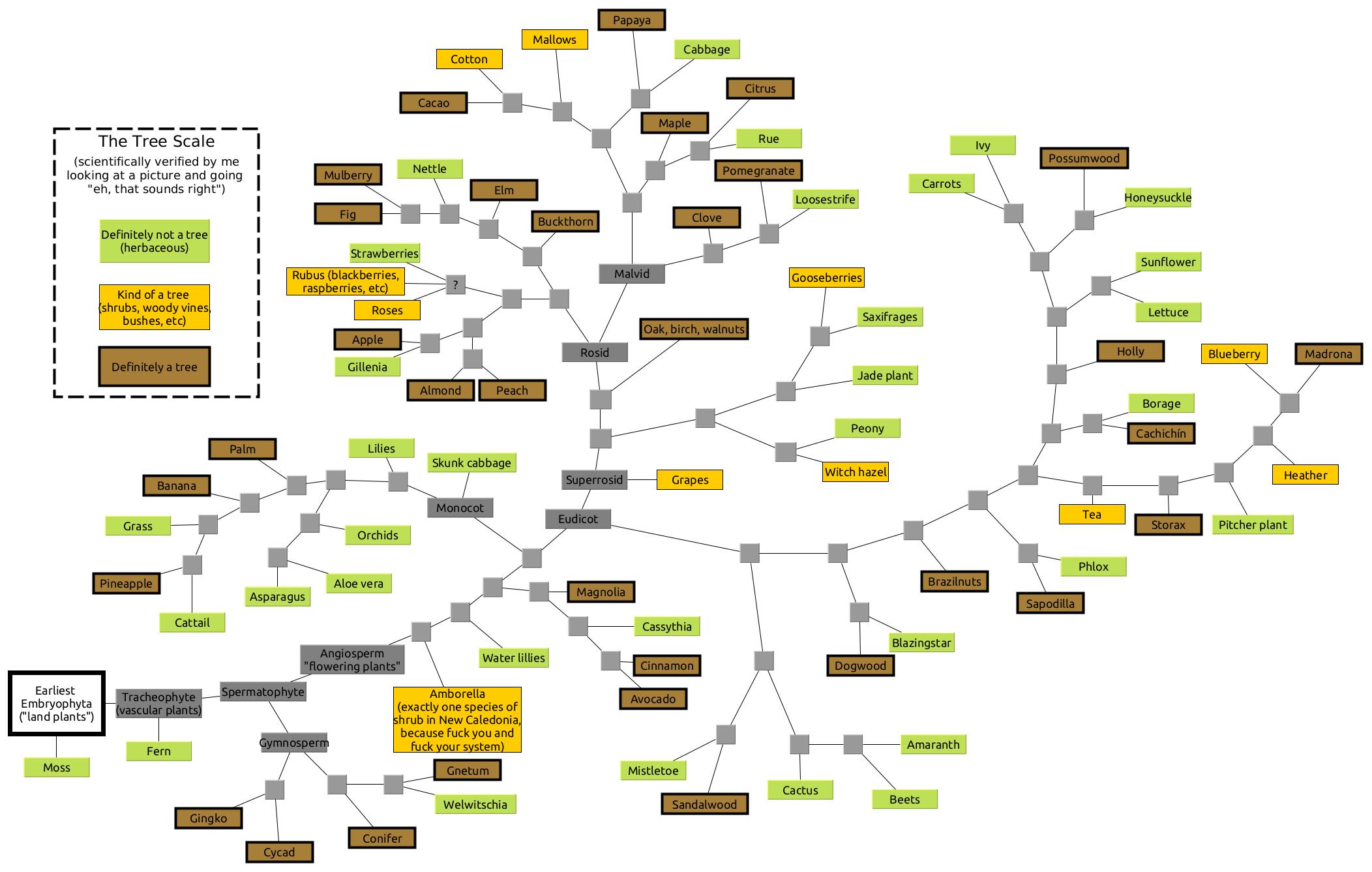

That poor soil is also why the olive tree was relied on for oil instead of grains, which had better yields and took way less time to reach producing age. You could grow olive trees in places you couldn’t farm grain. And now we all know and love the oil from this tree. A tree is a wild place to get oil from! Similar story for grapevines.

- The Spartans really liked this specific pork and blood soup called “black broth”.

This book was a fun read, on top of the cool history. Laudan has a straightforward listful way of describing cuisines that really puts me in the mind of a Redwall or a George R. R. Martin feast description.

A royal meal in the Indian Mauryan Empire (circa 300 BCE or so):

For court meals, the meat was tempered with spices and condiments to correct its hot, dry nature and accompanied by the sauces of high cuisine. Buffalo calf spit-roasted over charcoal and basted with ghee was served with sour tamarind and pomegranate sauces. Haunch of venison was simmered with sour mango and pungent and aromatic spices. Buffalo calf steaks were fried in ghee and seasoned with sour fruit, rock salt, and fragrant leaves. Meat was ground, formed into patties, balls, or sausage shapes, and fried, or it was sliced, dried to jerky, and then toasted.

Or in around 600 CE, Mexican Teotihuacan eating:

To maize tamales or tortillas were added stews of domestic turkeys and dogs, and deer, rabbits, ducks, small birds, iguanas, fish, frog, and insects caught in the wild. Sauces were made with basalt pestles and mortars that were used to shear fresh green or dried and rehydrated red chiles, resulting in a vegetable puree that was thickened with tomatillos (Physalis philadelphica) or squash seeds. Beans, simply simmered in water, provided a tasty side dish. For the nobles, there were gourd bowls of foaming chocolate, seasoned with annatto and chili.

I’m a vegetarian who has no palette for spice and now all I can think about is eating dog stew made with sheared fresh green chiles and plain beans.

Be careful about reading this book while broke on an airplane. You will try to convince yourself this is all academic and that you’re not that curious about what iguana meat tastes like. You’ll lose that internal battle. Then, in desperation, your brain will start in on a new phase. You’ll tell yourself as you scrape the last of your bag of traveler’s food – walnut meat, dried grapes, and pieces of sweet chocolate – that you wait to be brought a complimentary snack of baked wheat crackers flavored with salt, and a cup of hot coffee with cow’s milk, sweetened with cane sugar, and also that this is happening while you are flying. In this moment, you will be enlightened.

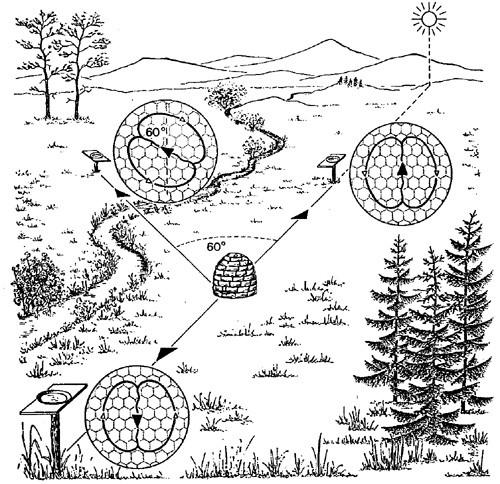

Grindstones are very important throughout history. A lot of cultures used hand grindstones at first and worked into water or animal-driven mills later. You grind grain to get flour, but you also grind things to get oil, spices, a different consistency of root, etc. You spent a lot of time grinding grain. There are a million kinds of hand grindstone. Some are still used today. When Roman soldiers marched around continents, they brought with them a relatively efficient rotary grindstone. They used mules to carry one 60-pound grindstone per 8 people. Every day, a soldier would grind for an hour and a half to feed the eight people. The grain would be stolen from storehouses conquered along the way.

Chapter 3 on Buddhist cuisines throughout Asia was especially great. Buddhism spread as sort of a reaction to the high sacrificial meat-n-grain cuisine of the time – a religious asceticism that really caught on. Ashoka spread it in India in 250 BCE, and slowly over centuries seeped into China. Buddhists did not kill animals (mostly) nor drink alcohol, and ate a lot of rice. White rice, sugar, and dairy spread through Asia. In both China and India, as the rich got into it, Buddhism became its own new high cuisine: rare vegetables, sugar, ghee and other dairy, tea, and elaborate vegetarian dishes. So much for asceticism!

There is an extensive history of East Asian tofu and gluten-based meat substitutes that largely came out of vegetarian Buddhist influence. A couple 1100s and 1200s CE Chinese cookbooks are purely vegetarian and have recipes for things like mock lung (you know, like a mock hamburger or mock chicken, but if you’re missing the taste of lung.) (You might be interested in modern adaptations from Robban Toleno.)

Diets often go with religion. It’s a classic way to divide culture, and also, food and philosophy and ideas about health have always gone hand in hand in hand. Islamic empires spread cuisine over the middle east. Christian empires brought their own food with them to other parts of the world.

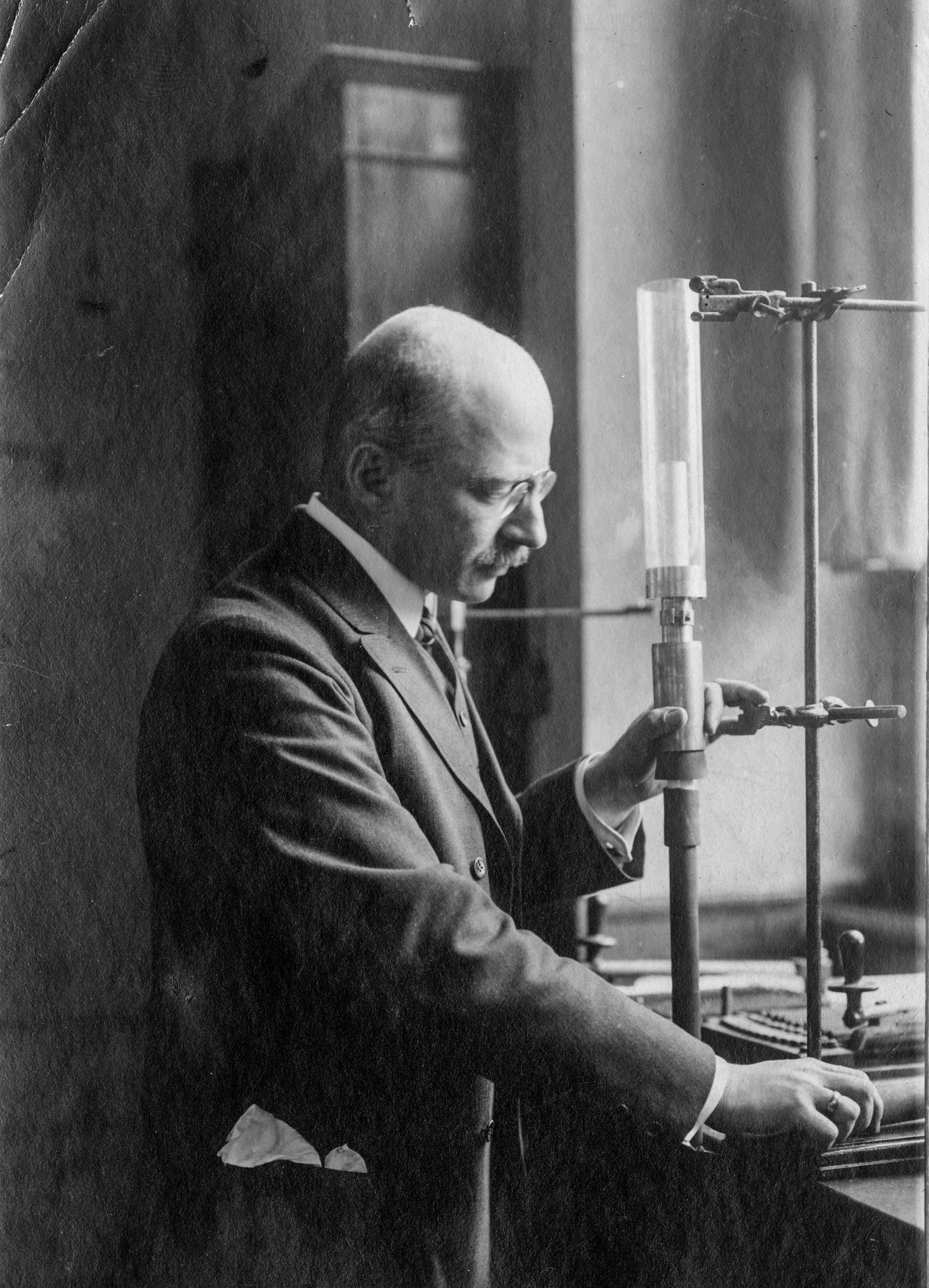

A lot of early cuisines in Europe, the Middle East, India, Asia, and Mesoamerica were based on correspondences between types of food and elements and metaphysical ideas. You would try to reach balance. In Europe in the 1500s, during the Enlightenment, these old incorrect ideas about nutrition were replaced with bold new incorrect ideas about nutrition. Instead of corresponding to four elements, food was actually made of three chemical elements: salt, oil, and vapor. The Dutch visionary Paracelsus who thought chemistry could be based on the bible and was a century later called a “master at murdering folk with chemistry”.

Fermenting took on its own magic:

Paracelsus suggested that “ferment” was spiritual, reinterpreting the links between the divine and bread in terms of his Protestant chemistry. When ferment combined with matter (massa in Latin, significantly also the word for bread dough), it multiplied. If this seems abstract, considered what happened in bread making. Bakers used a ferment or leaven[…] and kneaded it with flour and water. A few hours later, the risen dough was full of bubbles, or spirit. Ferment, close to the soul itself, turned lifeless stuff into vibrant, living bodies filled with spirit. The supreme example of ferment was Christ, described by the chemical physicians as fermentum, “the food of the soul.”

Again, cannot stress enough that the details of this food cosmology still got most things wrong. But I think they weren’t far off with this one.

There was an article I had bookmarked years ago about the very early days of microbiology and how many people interpreted this idea of tiny animalcules found in sexual fluid and sperm as literal demons. Does anyone know about this? I feel like these dovetail very nicely in a history of microbiological theology.

Corn really caught on in the 1800s as a food for the poor in East and Central Africa, Italy, Japan, India, and China. I don’t really know how this happened. I assume it grew better in some climates than native grains, like potatoes did in Europe?

Corn cuisine in the Americas knew to treat the corn with lye to release more of its nutrients, kill toxins, and make it taste better. This is called nixtamalization. When corn spread to Eurasia, it was grown widely, but nixtamalization didn’t make it over. The Eurasian eaters had to get those nutrients from elsewhere. They still ate corn, but it was a worse time!

- In Iceland, where no crops would grow, people would use dried fish called “stockfish” and spread sheep butter on it and eat it instead of bread.

Caloric efficiency was a fun recurring theme. See again, the slow adoption of the potato into Europe. Cuisine has never been about maximizing efficiency. Once bare survival is assured, people want to eat what they know and what has high status in their minds.

I think this is a statement about the feedback cycles of individual people, for instance, subsistence farmers. Suppose you’re a Polish peasant in 1700 and you struggle by year by year growing wheat and rye. But this year you have access to potatoes, a food you somewhat mistrust. You might trust it enough to eat a cooked potato handed to you if you were starving – but when you make decisions about what to plant for a year, you will be reluctant to commit to you and your family to a diet of a possibly-poisonous food (or to a failed crop – you don’t know growing potatoes either). Even if it’s looking like a dry year – especially if it’s looking like a dry year! – you know wheat and rye. You trust wheat and rye. You’ve made it through a lean year of wheat and rye before. You’ll do it again.

People are reluctant to give up their staple crops but they will supplant them. Barley was solidly replaced by the somewhat-more-efficient wheat throughout Europe, millet by rice and wheat in China. But we settled on some ones we like:

The staples that humans had picked out centuries before 1000 B.C.E. still provide most of the world’s human food calories. Only sugarcane, in the form of sugar, was to join them as a major food source.

Around 1650 in Europe, protestant-derived French cuisine overtook high Catholic cuisine as the main food of the European aristocracy.

| Catholic cuisine | French cuisine |

| Roasts Fancy pies Pottage Cold foods are bad for you Fasting dishes Lard | Pastry Fancy sauces Boullions and extracts Raw salads Focus on vegetables Butter |

Slowly coming up in more recent times, say the 1700s, was a very slow equalizing in society:

As more nations followed the Dutch and British in locating the source of rulers’ legitimacy not in hereditary or divine rights but in some form of consent or expression of the will of the people, it became increasingly difficult to deny to all citizens the right to eat the same kind of food.

After the French revolution, high French cuisine was almost canceled in France. Everyone should eat as equals, even if the food was potatoes! Fortunately Unfortunately As it happened, Napoleon came in after not too long and imperial high cuisine was back on a very small number of menus.

Speaking of potatoes and self-governance:

The only place where potatoes were adopted with enthusiasm was in distant [from Europe] New Zealand. The Maoris, accustomed to the subtropical roots that they had introduced to the North Island, welcomed them when introduced by Europeans in the 1770s because they grew in the colder South Island. Trading potatoes for muskets with European whalers and sealers enabled the Maoris to resist the British army from the 1840s to the 1870s.

Meanwhile, in Europe: Hey, we’re back to meat and grain! Britain really prized itself on beef and attributed the strength of its empire to beef. Even colonized peoples were like “whoa, maybe that beef and bread they’re eating really is making them that strong, we should try that.” Here’s a 1900 ad for beef extract that aged poorly:

That said, I did enjoy Laudan’s defense of British food. Starting in 1800, the British Empire was well underway, and what we now think of as stereotypical British cuisine was developing. It was heavy in sugar and sweets, white bread, beef, and prepared food. During the early industrial revolution, food and nutrition and the standard of living went down, but by the 1850s, all of it really came back.

It is worth noting that few cuisines have been so roundly condemned as nutritional and gastronomical disasters as British cuisine.

But Laudan points out that this food was not the aristocrat food (they were still eating French cuisine). It was the food of the working city poor. This is the rise of the “middling cuisines”, a true alternative between fancy high cuisine of a truly tiny percent of society and humble cuisine of peasants who often faced starvation. For once, they had enough to eat. This was new.

After discussing the various ways in which the diet may have been bland or unappealing compared to neighboring cuisines –

Nonetheless, from the perspective of the urban salaried and working classes, the cuisine was just what they had wished for over the centuries: white bread, white sugar, meat, and tea. A century earlier, not only were these luxuries for much of the British population, but the humble were being encouraged to depend on potatoes, not bread, a real comedown in a society in which some kind of bread, albeit a coarse one, had been central to well-being for centuries. Now all could enjoy foodstuffs that had been the privilege of the aristocracy just a few generations earlier. Indeed, the meal called tea came close to being a true national cuisine. Even though tea retained traces of class distinctions, with snobberies about how teacups should be held, or whether milk or tea should be put into the cup first, everyone in the country, from the royal family, who were painted taking tea, to the family of a textile worker in the industrial north of the country, could sit down to white bread sandwiches or toast, jam, small cakes, and an iced sponge cake as a centerpiece. They could afford the tea that accompanied the meal. Set out on the table, tea echoed the grand buffets of eighteenth-century French high cuisine. [...] What seemed like culinary decline to those Britons who had always dined on high or bourgeois cuisine was a vast improvement to those enjoying those ampler and more varied cuisines for the first time.

[...]

Although to this day food continues to be used to reinforce minor differences in status, the hierarchical culinary philosophy of ancient and traditional cuisines was giving way to the more egalitarian culinary philosophy of modern cuisines.

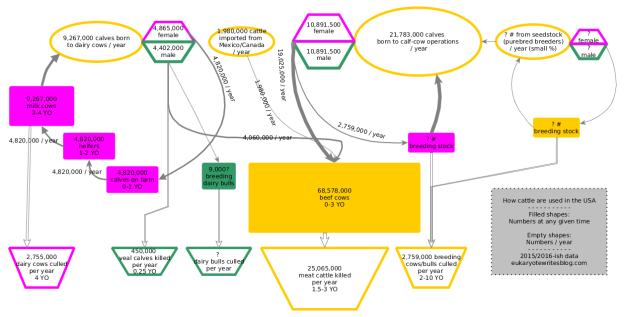

A lot of this was facilitated by imperialism and/or outright slavery. The tea itself, for instance. But Britain was also deeply industrialized. Increased crop productivity, urbanization, and industrial processing were also making Britain’s home-grown food – wheat, meat – cheaper too. Or bringing these processes home. At the start of this period, sugar had been grown and harvested by slaves to feed Europe’s appetites, but in 1800, Prussian inventors figured out how to make sugar at scale from beets.

The work was done by men paid salaries or wages, not by slaves or indentured laborers. The sugar was produced in northern Europe, not in tropical colonies. And the price was one all Europeans could afford.

This was the sugar the British were eating then. Industrialization offered factory production of foods, canning, wildly cheap salt, and refrigeration.

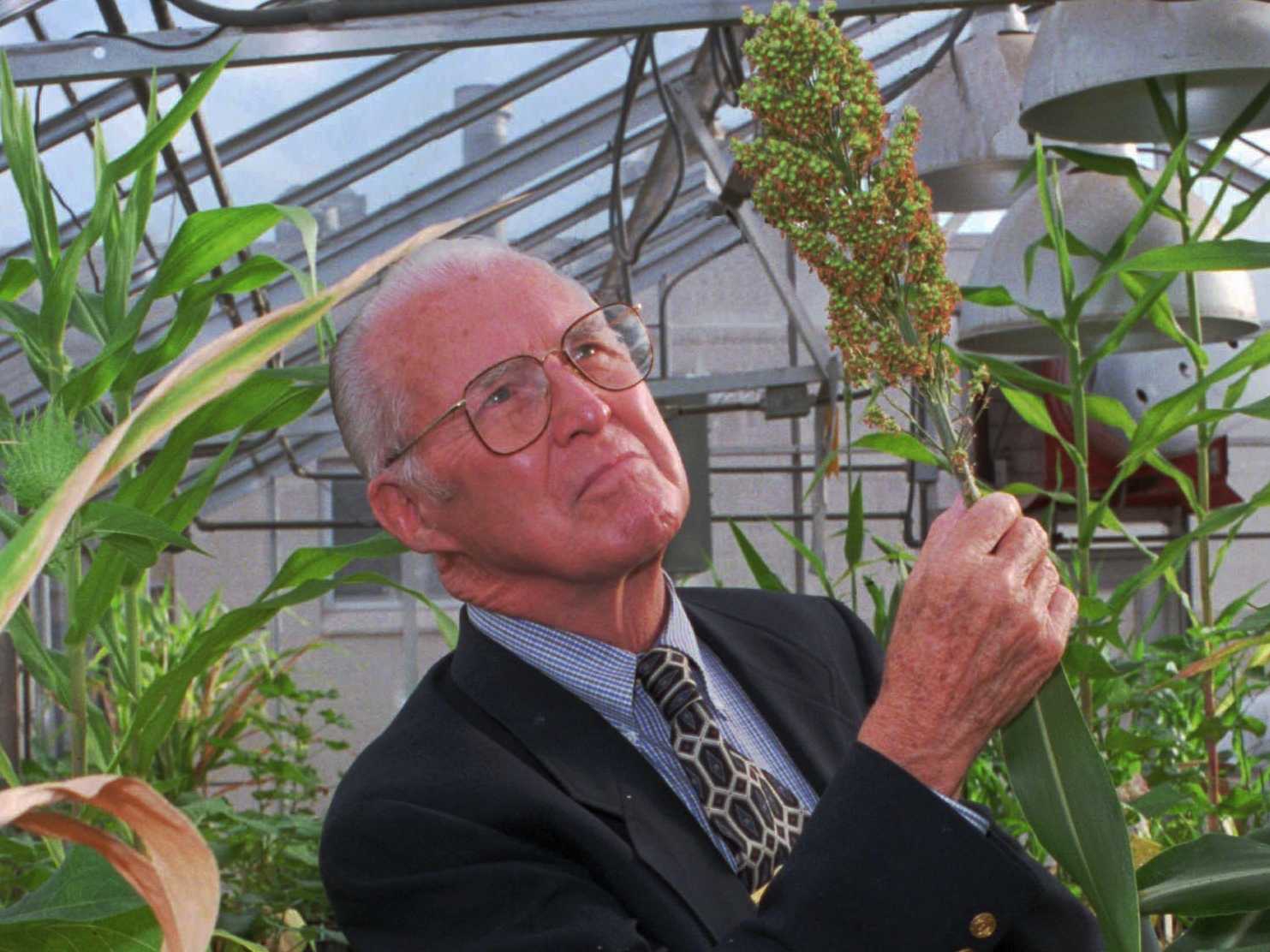

We’re reaching the modern age, where the empires have shrunk and most people get enough calories and have access to industrially-cheap food and the fruits of global trade. Laudan discusses at length the hamburger and instant ramen – wheat flour, fat, meat or meat flavor, low price, and convenience. New theories of nutrition developed and we definitely got them right this time. The empires break up and worldwide leaders take pride in local cuisines, manufacturing a sense of identity through food if needed. Most people have the option of some dietary diversity and a middling cuisine. Go back to that list of things people like to eat. Most of us have that now! Nice!

- Nigeria is the biggest importer of Norwegian stockfish. It caught on as a relief food delivered during Nigeria’s Biafran civil war. Here’s a 1960s photo of a Nigerian guy posing in a Bergen stockfish warehouse.

Aw, wait, is this a book review? Book review: Great stuff. There’s a lot of fascinating stuff not included in this summary. I wish it had more on Africa but I did like all the stuff about Eurasia that was in there. I feel like there are a few cultures with really really meat heavy cuisines – like Saami or Inuit cuisine – that could have been at least touched on. But also those aren’t like major cuisines and I can just learn about those on my own. Overall I appreciated the unwavering sense of compassion and evenhandedness – discussing cuisines and falsified theories of nutrition without casting judgment. Everyone’s just trying to eat dinner.

Rachel Laudan also has a blog. It looks really cool.

The book is “Cuisine and Empire” by Rachel Laudan, 2012. h/t my friend A for the recommendation.

More food history from Eukaryote Writes Blog: Triptych in Global Agriculture.

If you want to support my work by chucking me a few bucks per post, check out my Patreon!