[Content warning: discussion of violence and child abuse. No graphic images in this post, but some links may contain disturbing material.]

In July 2017, a Facebook user posts a video of an execution. He is a member of the Libyan National Army, and in the video, kneeling on the ground before his brigade, are twenty people dressed in prisoner orange and wearing bags over their heads. In the description, the uploader states that these people were members of the Islamic State. The brigade proceeds to execute the prisoners, one by one, by gunshot.

The videos was uploaded along with other executions perhaps as a threat or a boast, but it also becomes evidence, as the International Criminal Court orders an arrest warrant on the brigade’s Leader, Mahmoud Mustafa Busayf Al-Werfalli, for killing without due cause or process – the first warrant they have issued based only on social media evidence. And once the video falls into the lap of international investigative journalism collective Bellingcat, the video also becomes a map leading straight to them.

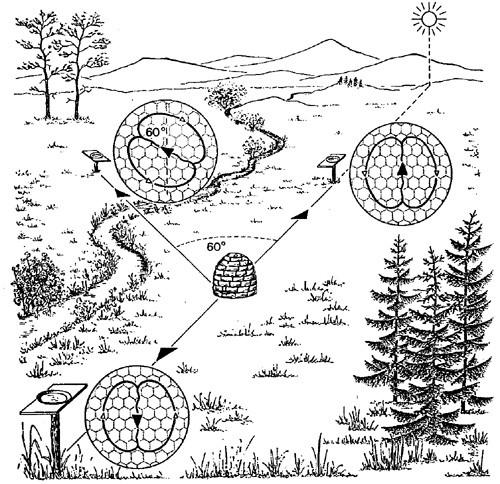

The video’s uploader is aware that they’re being hunted, and very intentionally, does not disclose the site the incident took place at. The camera focuses on an almost entirely unrecognizable patch of scrubby desert – almost entirely. At seconds, bits of horizon pop into the video, showing the edge of a fence and perhaps the first floor of a few buildings.

Bellingcat reporters knew the brigade was operating in the area around Benghazi, Libya’s second largest city. The long shadows of the prisoners in the video suggest the camera was facing one of two directions, in either early morning or late afternoon.

A Twitter user suggested that the sand color resembled that in the southwest of the city moreso than in other parts. The partial buildings glimpsed in the background looked only partly constructed, and within that district of the city, a great deal of construction had stopped do to the civil war. Rebel fighters were rumored to be living in a specific set of buildings – perhaps the same brigade? Using satellite footage, the researchers worked backwards to find where the video must have been shot, such that it could see both a fence, a matching view of a building, and other details like large shrubs. They came back with GPS coordinates, accurate out to six digits, and a date and time down to the minute.

The grim confirmation came when the coordinates were checked against a more recent set of satellite imagery from the area. In the newer footage, on the sand, facing out into the buildings, fence, and large shrubs, were fifteen large bloodstains.

Bellingcat is an organization that does civilian OSINT. OSINT is “Open Source Intelligence”, a name that comes to it from the national intelligence sphere where the CIA and FBI practice it – relevant knowledge that is gathered from openly available sources rather than from spy satellites, hacking, and the like. (OSINT is also a concept in computer security, I believe that’s related but probably a somewhat different context.) Civilian OSINT is to OSINT as citizen science is to science at large – democratized, anyone can do it, albeit perhaps fewer tools than the professionals tend to have. Given that OSINT inherently runs on public material, civilian OSINT has theoretical access to the exact same information that professionals have.

Bellingcat is, of course, an organization that employs OSINT experts (making them professionals), but they also have a commitment to openness and sharing their methods, which I believe classes them in with other. Organizations that focus on this are thin on the ground. (Outside of academia, where certain research on e.g. internet communities could be said do be doing the same thing.) For instance, the Atlantic Council has the Digital Forensics Research (DFR) Lab, which analyzes social media and other internet material in relation to global events.

Other OSINT organizations are less institutional and may be volunteer-based. Europol’s “Find an Object” program crops identifying information from pictures of child abuse, so that only items in the photo are visible (a package of cleaner, a logo on a hat) and then asks the internet if can identify the items and where they are found. WarWire is a network of professionals who gather and analyze social media data from warzones. Trace Labs is a crowdsourced project that finds digital evidence on missing persons cases, the results of which it sends to law enforcement. DNA Doe is a related project where volunteers use genetic evidence to identify unidentified bodies. Less formally, there are dedicated forums like WebSleuths and the “Reddit Bureau of Investigation” (r/RBI).

More often, though, these investigations emerge spontaneously and organically: More commonly, these efforts are not practiced or planned, but form spontaneously and organically – Reddit communities have occasionally made the news for identifying decades-old John Does, stabilizing shakey cell phone footage that provided important evidence in the case of a police shooting, and identifying that a mysterious electrical component in a user’s extension cord was a secret camera.

Volunteers

Volunteer labor is an elegant fit for OSINT:

- Much of it is digital and doable remotely

- Many tasks require little training

- Depending on the cause, volunteers will work

- Causes are things people care about

- Volunteers work at their own hours and are thus resilient to the kind of emotional burnout bellingcat has seen in its employees

- Willing to devote their time

Let’s unpack ‘time.’ Many investigations come down, eventually, to monotonous searches: Bellingcat was eventually able to use just five photos with vague landscape features to pinpoint two geographic locations where human trafficking had taken place for the “Trace an Object” project. A remarkable task – and one that took weeks.

(Steps in the process included “exploring major cities in Southeast Asia via Google Streetview to find ones that looked most similar to photos”, and “guessing that the closest-looking city was the correct one”. This worked.)

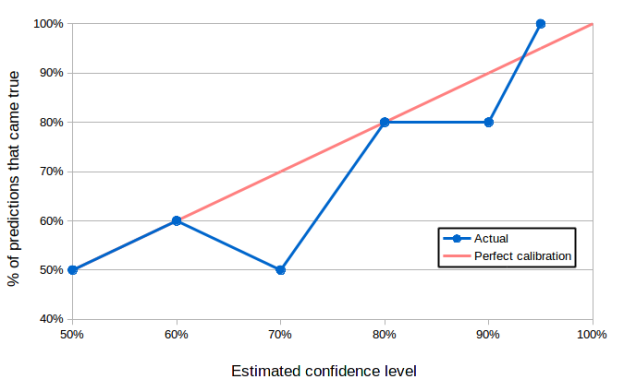

Overall, they spent over 2,500 hours to concretely identify 12 Europol photos in the past twelve months, and to partially identify thirteen more. And identification of objects is only one step in the way to arrest – some photographs were years old, the perpetrators and victims likely moved or worse. In the Europol program’s three year history, with tens of thousands of volunteer tips, only ten children have been rescued.

Any child saved from these horrors is, of course, a success. But it suggests that paying people for this type of work isn’t going to be efficient in the standard effective altruism framework of lives-saved per dollar.

I think practical civilian OSINT, to move monotonous mountains like this one, needs to tap into a different reservoir: the kind of digital energy that has built and maintained Wikipedia, countless open-source projects, the universe of fanpages and fanfiction, etc. This sort of collaborative, enthusiastic volunteer labor is well suited to the more repetitive and time-consuming aspects of open source investigation.

(Obviously, different projects will have different payoffs – I’m sure that some will be hugely effective per paid hour, although I don’t know which ones they are.)

Sidenote: What about automating OSINT with neural nets?

I bring this up because I know my audience, and I know people are going to go “wait, image identification? You know DeepMind can do that now, right?”

Well: the neural nets for this don’t exist yet. If someone wants to make them, I could see that being beneficial for OSINT, although I’d advise such a person to take a long hard look at the ‘OSINT is a dual use technology’ section of this post below, and to think long and hard about possible government and military uses for such a technology (both your own government and others.) I suspect this capability is coming either way, either from the government or commercial AI companies, and so may be a moot issue.

Still, I’m talking specifically about what OSINT can be used for now.

OSINT is a dual-use technology

In biology and other fields, a “dual-use” technology is one that can be used for good as well as for evil. A machine that synthesizes DNA, for instance, can be used to make medical research easier, and it can be used to make bioterror easier.

Civilian OSINT is one. While Reddit has identified missing persons, its communities also famously misidentified an innocent man as the Boston Marathon Bomber. Data gathered from a bunch of untrained unvetted internet randos should probably be viewed with some skepticism.

It’s also tragically easy to misuse. A lot of OSINT tools (for e.g. identifying people across social media) could be used by stalkers, abusers, authoritarian governments, and other bad actors just as trivially as it could by investigators. Raising the profile of these methods would expose them to misuse. Improving on OSINT tools would expose them to misuse.

If it helps, I think most small-scale efforts – like anything by Reddit or Trace Labs – are not really doing anything that large governments can’t do, technically speaking.* Ethical civilian OSINT projects should also be expected to go out of their way to demonstrate that they’re using volunteer labor ethically and for a specific purpose.

That leaves the threat as ‘malicious civilians’ (stalkers, etc.) and perhaps ‘resource-limited local governments’. This is a significant issue.

* (Though they can do things that large governments can’t do, time- and resource-wise. Keep reading.)

But here’s why we should use it anyway

Standard police and journalistic investigations (as two common uses of intelligence)are also very fallible. They may rely on misinformation and guesswork, poor eyewitness testimony, faulty drug tests, error-prone genetic methods, and debunked psychological methods. It’s not obvious to me that the average large-group civilian OSINT investigation will have a higher rate of false negatives than a standard investigation.

Moreover, that’s not really the issue. The relevant question is not “is crowd-sourced civilian OSINT worse than conventional investigation?” It’s “is crowd-sourced civilian OSINT worse than no investigation at all?” When Europol puts objects from images of child abuse online and asks for anyone who can identify the objects, and an answer is found and confirmed with online information, Europol workers could also have done that. It just would have taken them too high of a cost in time and human effort. When Reddit users solve cold cases, they are explicitly aiming for cases that are no longer under investigation by the police, or cases where police are under-investigating.

Open investigations like Bellingcat also structurally facilitate honesty because their work can be independently verified – all of the reasoning and evidence for a conclusion is explicitly laid out. In this way, civilian OSINT shares the ideals of science, and benefits because of it.

Where OSINT shines

It seems like cases where civilian OSINT works best have a few properties:

Not rushed. Reddit’s misidentification of the Boston Marathon Bomber happened within that hours after the attack. People were rushing to find an answer.

Results are easily verifiable. For instance, when Europol receives a possible identification of a product in an image, they can find a picture of that product and confirm.

Structure and training. An intentional, curated, organized effort is more likely to succeed than a popcorn-style spontaneous investigation a la Reddit. For instance, it’s probably better for investigations to have a leader. And a method. Many OSINT skills are readily teachable.

Learning OSINT

Despite the rather small number of public and actively-recruiting OSINT projects, there are a few repositories of OSINT techniques.

The Tactical Technology Collective, a Berlin nonprofit for journalists and activists, created Exposing the Invisible: a collection of case studies and techniques for performing digital OSINT research, especially around politics.

Bellingcat also regularly publishes tutorials on its methods, from using reverse image searches to identifying missiles to explaining your findings like a journalist.

The nonprofit OSINT Curious bills itself as a “learning catalyst” and aims to share OSINT techniques and make it approachable. They produce podcasts and videos demonstrating digital techniques. In addition, a variety of free tools intentionally or purposefully facilitate various OSINT practices, and various repositories collect these.

OSINT for effective altruism?

I don’t actively have examples where OSINT could be used for effective causes, but I suspect they exist. It’s a little hard to measure OSINT’s effectiveness since, as I described above, many OSINT tasks are a bad go from a reward-per-hour perspective. But they can use hours that wouldn’t be used otherwise, from people’s spare time or (more likely) by attracting people who wouldn’t otherwise be in the movement.

At the Minuteman Missile Site museum in South Dakota, I read about a civilian effort by peace activists during the Cold War to map missile silos in the Midwest. Then they published them and distributed the maps rurally. The idea was that if people realized that these instruments of destruction were so close to them, they might feel more strongly about them, or work to get them “out of our backyard.” (In a way, exploiting the Copenhagen interpretation of ethics.) Did this work? No idea. But it’s an OSINT-y project that touches on global catastrophic risk, and it’s certainly interesting.

I wondered if one could do a similar thing by mapping the locations of factory farms in the US, and thus maybe instill people to act locally to reform or remove them. The US Food and Water Watch had such an interactive digital map for the USA, but it seems to have gone down with no plans to bring it back. Opportunity for someone else to do so and give it some quality PR?

(In the mean time, here’s one for just North Carolina, and here’s a horrifying one for Australia.)

Again, I don’t know how effective it would be as a campaigning move, but I could imagine it being a powerful tool. The point I want to make is basically “this is an incredible tool.” Try thinking of your own use cases, and let me know if you come up with them.

A shot at – not utopia, but something decent

Here’s my last argument for civilian OSINT.

Trace Labs staff have pointed out that their teams tend to be more successful at finding evidence about people who have recently gone missing, versus people who have gone missing – say – over a decade ago. This is because people in the modern age are almost guaranteed to have extensive web presences. Not just their own social media but the social media of relatives and friends, online records, phone data, uploaded records, digitized news… There used to be no centralized place for the average person to find this info for a far-off stranger. Information was stored and shared locally. Now, teenagers half a world away can find it.

I have a lot of hope and respect for privacy and privacy activists. I think basic digital privacy should be a right. But the ship is sailing on that one. Widespread technology gives governments a long reach. China is using facial recognition AI to profile a racial minority. The technology is there already. A lot of social media identification is in public. A lot of non-public conversation is already monitored in some form or another; that which isn’t can often be made public to governments without too much effort. US federal agencies are hiding surveillance cameras in streetlights. You can encrypt your messages and avoid having your photo taken, but that won’t be enough for long. It’s already not. As long as citizens are happy to keep carrying around internet-connected recording and location-tracking devices, and uploading personal material to the web – and I think we will – governments will keep being able to surveil citizens.

Sci-fi author and futurist David Brin also thinks that this is close to inevitable. But he sees this balanced by the concept of ‘reciprocal transparency’: the idea that the tools that enable government surveillance, the cameras and connectivity and globally disseminated information, can also empower citizens to monitor the government and expose corruption and injustice.

A reciprocally transparent society could be a very healthy one to live in. Maybe not what we’d prefer – but still pretty good. Civilian OSINT seems like the best shot at that we have right now: Open, ubiquitous, and democratized.