Part 1: The anomaly

This story starts, as many stories do, with my girlfriend 3D-printing me a supernatural artifact. Specifically, one of my favorite SCPs, SCP-184.

We had some problems with the print. Did the problems have anything to do with printing a model of a mysterious artifact that makes spaces bigger on the inside, via a small precisely-calibrated box? I would say no, there’s no way that be related.

Anyway, the image used for the SCP in question, and thus also the final printed model, is based a Roman dodecahedron. Roman dodecahedrons are a particular shape of metal object that have been dug up in digs from all over the Roman period, and we have no idea why they exist.

Many theories have been advanced. You might have seen these in an image that was going around the internet, which ended by suggesting that the object would work perfectly for knitting the fingers of gloves.

There isn’t an alternative clear explanation for what these are. A tool for measuring coins? A ruler for calculating distances? A sort of Roman fidget spinner? This author thinks it displays a date and has a neat explanation as for why. (Experimental archaeology is so cool, y’all.)

Whatever the purpose of the Roman dodecahedron was, I’m pretty sure it’s not (as the meme implies is obvious) for knitting glove fingers.1

Why?

1: The holes are always all different sizes, and you don’t need that to make glove fingers.

2: You could just do this with a donut with pegs in it, you don’t need a precisely welded dodecahedron. It does work for knitting glove fingers, you just don’t need something this complicated.

3: The Romans hadn’t invented knitting.

Part 2: The Ancient Romans couldn’t knit

Wait, what? Yeah, the Romans couldn’t knit. The Ancient Greeks couldn’t knit, the Ancient Egyptians couldn’t knit. Knitting took a while to take off outside of the Middle East and the West, but still, almost all of the Imperial Chinese dynasties wouldn’t have known how. Knitting is a pretty recent invention, time-wise. The earliest knit objects we have are from Egypt around 1000 CE.

This is especially surprising because knitting is useful for two big reasons:

First, it’s very easy to do. It takes yarn and two sticks and children can learn how. This is pretty rare for fabric manufacturing – compare, for instance, weaving, which takes an entire loom.

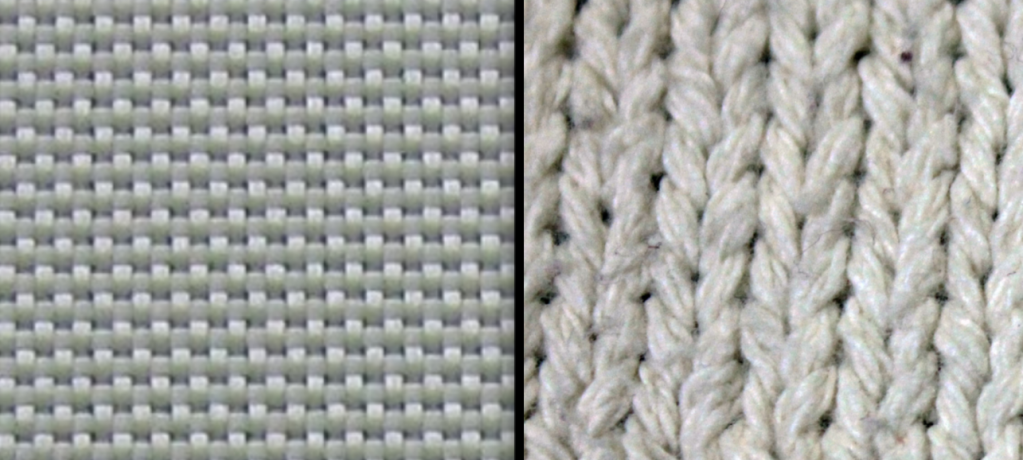

Sidenote: Do you know your fabrics? This next section will make way more sense if you do.

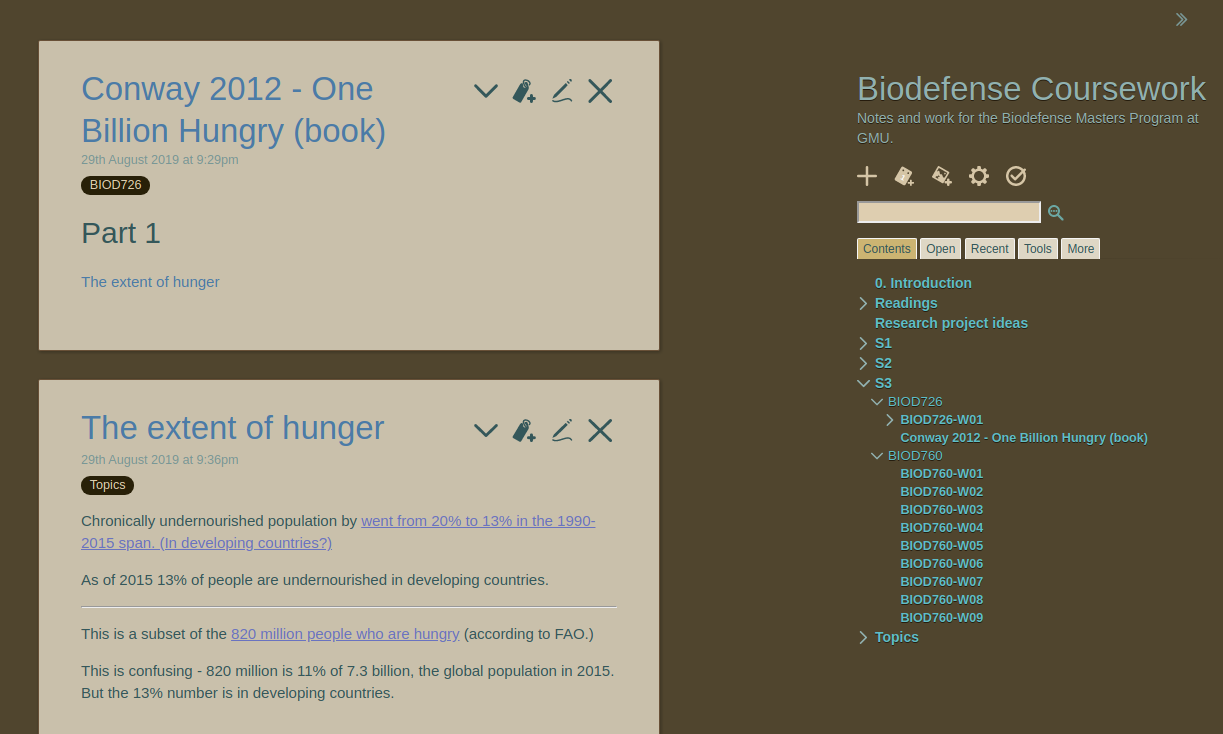

| Woven fabric | Knit fabric |

| Commonly found in: trousers, collared/button up shirts, bedsheets, dish towels, woven boxers, quilts, coats, etc. Not stretchy. Loose threads won’t make the whole cloth unravel. | Commonly found in: T-shirts, polo shirts, leggings, underwear, anything made of jersey fabric, sweaters, sweatpants, socks. Stretchy. If you pull on a lose thread, the cloth unravels. |

Second, and oft-underappreciated, knitted fabric is stretchy. We’re spoiled by the riches of elastic fabric today, but it wasn’t always so. Modern elastic fabric uses synthetic materials like spandex or neoprene; the older version was natural latex rubber, and it seems to have taken until the 1800s to use rubber to make clothing stretchy. Knit fabric stretches without any of those.

Before knitting, your options were limited – you could only make clothing that didn’t stretch, which I think explains a lot of why medieval and earlier clothing “looks that way”. A lot of belts and drapey fabric. If something is form-fitting, it’s probably laced. (…Or just more-closely tailored, which unrelatedly became more of a thing later in the medieval period.)

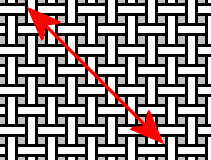

You could also use woven fabric on the bias, which stretches a little.

Medieval Europe made stockings from fabric cut like this. Imagine a sock made out of tablecloth or button-down-shirt-type material. Not very flexible. Here’s a modern recreation on Etsy.

Other kinds of old “socks” were more flexible but more obnoxious, made of a long strip of bias-cut fabric that you’d wrap around your feet. (Known as: winingas, vindingr, legwraps, wickelbänder , or puttees.) Historical reenactors wear these sometimes. I’m told they’re not flexible and restrict movement, and that they take practice to put on correctly.

Come 1000 CE, knitting arrives on the scene.

Which is to say, it’s no surprise that the first knitted garments we see are socks! They get big in Europe over the next 300 years or so. Richly detailed bags and cushions also appear. We start seeing artistic depictions of knitting for the first time around now too.

Interestingly, this early knitting was largely circular, meaning that you produce a tube of cloth rather than a flat sheet. This meant that the first knitting was done not with two sticks and some yarn, but four sticks and some yarn. This is much easier for making socks and the like than using two needles would be. …But also means that the invention process actually started with four needles and some yarn, so maybe it’s not surprising it took so long.2

(Why did it take so long to invent knitting flat cloth with two sticks? Well, there’s less of a point to it, since you already have lots of woven cloth, and you can do a lot of clothes – socks, sweaters, hats, bags – by knitting tubes. Also, by knitting circularly, you only have to know how to do one stitch (the knit stitch) whereas flat knitting requires you also use a different stitch (the perl stitch) to make a smooth fabric that looks like and is as stretchy as round knitting. If you’re not a knitter, just trust me – it’s an extra step.)

(You might also be wondering: What about crochet? Crochet was even more recent. 1800s.)

Part 3: The Ancient Peruvians couldn’t knit either, but they did something that looks the same

You sometimes see people say that knitting is much older, maybe thousands of years old. It’s hard to tell how old knitting is – fabric doesn’t always preserve well – but it’s safe to say that it’s not that old. We have examples of people doing things with string for thousands of years, but no examples of knitting before those 1000 CE socks. What we do have examples of is naalbinding, a method of making fabric from yarn using a needle. Naalbinding produces a less-stretchy fabric than knitting. It’s found from Scandinavia to the Middle East and also shows up in Peru.

The native Peruvian form of naalbinding is a specific technique called cross-knit looping. (This technique also shows up sometimes in pre-American Eurasia, but it’s not common.) The interesting thing about cross-knit looping is that the fabric looks almost identical to regular knitting.

Here’s a tiny cross-knit-looped bag I made, next to a tiny regularly knit bag I made. You can see they look really similar. The fabric isn’t truly identical if you look closely (although it’s close enough to have fooled historians). It doesn’t act the same either – naalbound fabric is less stretchy than knit fabric, and it doesn’t unravel.

The ancient Peruvians cross-knit-looped decorations for other garments and the occasional hat, not socks.

Inspired by the Paracas Textile figures above, I used cross-knit-looping to make this little fox lady fingerpuppet:

I think it was easier to do fine details than it would be if I were knitting – it felt more like embroidery – but it might have been slower to make the plain fabric parts than knitting would have been. But I’ve done a lot of knitting and very little cross-knit-looping, so it’s hard to compare directly. If you want to learn how to do cross-knit looping yourself, Donna Kallner on Youtube has handy instructional videos.

I wondered about naalbinding in general – does the practice predate human dispersal to the Americas, or did the Eurasian technique and the American technique evolve separately? Well, I don’t know for certain. Sewing needles and working with yarn are old old practices, definitely pre-dating the hike across Beringia (~18,000 BCE). The oldest naalbinding is 6500 years old, so it’s possible – but as far as I know, no ancient naalbinding has every been found anywhere in the Americas outside of Peru, or in eastern Russia or Asia – it was mostly the Middle East and Europe, and then, also, separately, Peru. The process of cross-knit looping shares some similarities with net-making and basket-weaving, so it doesn’t seem so odd to me that the process was invented again in Peru.

For a while, I thought, it’s even weirder that the Peruvians didn’t get to knitting – they were so close, they made something that looks so similar. But cross-knit-looping doesn’t actually particularly share any other similarities with knitting more than naalbinding or even more common crafts like basketweaving or weaving – the tools are different, the process is different, etc.

So the question should be the same for the Romans or any other other culture with yarn and sticks before 1000 AD: why didn’t they invent knitting? They had all the pieces. …Didn’t they?

Yeah, I think they did.

Part 4: Many stones can form an arch, singly none

Let’s jump topics for a second. In Egypt, a millenium before there were knit socks, there was the Library of Alexandria. Zenodotus, the first known head librarian at the Library of Alexandria, organized lists of words and probably the library’s books by alphabetical order. He’s the first person we know of to alphabetize books with this method, somewhere around 300 BCE.

Then, it takes 500 years before we see alphabetization of books by the second letter.3

The first time I heard this, I thought: Holy mackerel. That’s a long time. I know people who are very smart, but I’m not sure I know anyone smart enough to invent categorizing things by the second letter.

But. Is that true? Let’s do some Fermi estimates. The world population was 1.66E8 (166 million) in 500 BCE and 2.02E8 (202 million) in 200 CE. But only a tiny fraction would have had access to books, and only a fraction of those in the western alphabet system. (And of course, people outside of the Library of Alexandria with access to books could have done it and we just wouldn’t know, because that fact would have been lost – but people have actually studied the history of alphabetization and do seem to treat this as the start of alphabetization as a cultural practice, so I’ll carry on.)

For this rough estimate, I’ll average the world population over that period to 2E8. Assuming a 50 year lifespan, that’s 10 lifespans and thus 2E10 people living in the window. If only one in a thousand people would have been in a place to have the idea and have it recognized (e.g. access to lots of books), that’s 1 in 2E7 people, or 1 in 20 million. That’s suddenly not unreachable. Especially since I think “1 in 1,000 ‘being able to have the idea’” might be too high – and if it’s more like “1 in 10,000” or lower, the end number could be more like 1 in 1 million. I might actually know people who are 1 in 1 million smart – I have smart friends. So there’s some chance I know someone smart enough to have invented “organizing by the second letter of the alphabet”.

Sidenote: Ancient bacteria couldn’t knit

| A parallel in biology: Some organisms emit alcohol as a waste product. For thousands of years, humans have been concentrating alcohol in one place to kill bacteria. (… Okay, not just to kill bacteria.) From 2005 to 2015, some bacteria have been getting 10x resistant to alcohol. Isn’t it strange that this is only happened in the last 10 years? This question actually lead, via a winding path, to the idea that became my Funnel of Human Experience blog post. I forgot to answer the question, but suffice to say that if alcohol production is in some way correlated&&& with the human population, 10 years is more significant but still not very much. And yet, alcohol resistance seems to have involved in Enterococcus faecium only recently. The authors postulate the spread of alcohol handwashing. Seems as plausible as anything. Or maybe it’s just difficult to evolve. |

Knitting continues to interest me, because a lot of examples of innovation do rely heavily on what came before. To have invented organizing books by the second letter of the alphabet, you have to have invented organizing books by the first letter of the alphabet, and also know how to write, and have access to a lot of books for the second letter to even matter.

The sewing machine was invented in 1790 CE and improved drastically over the next 60 years, where it became widely used to automate a time-consuming and extremely common task. We could ask: “But why wasn’t the sewing machine invented earlier, like in 1500 CE?”

But we mostly don’t, because to invent a sewing machine, you also need very finely machined gears and other metal parts, and that technology also came up around the industrial revolution. You just couldn’t have made a reliable sewing machine in 1500 CE, even if you had the idea – you didn’t have all the steps. In software terms, as a technology, sewing machines have dependencies. Thus, the march of human progress, yada yada yada.

But as far as I can tell, you had everything that went into knitting for thousands of years beforehand. You had sticks, you had yarn, you had the motivation. Knitting doesn’t have dependencies after that. And you had brainpower: people in the past everywhere were making fiber into yarn and yarn into clothing all of the time, seriously making clothes from scratch takes so much time.

And yet, knitting is very recent. That was so big of a leap that it took thousands of years for someone to figure it out.

1 I’m not displaying the meme itself in this otherwise image-happy post because if I do, one of my friends will read this essay and get to the meme but stop reading before they get to the part where I say the meme is incorrect. And then the next time we talk, they’ll tell me that they read my blog post and liked that part where a Youtuber proved that this mysterious Roman artifact was used to knit gloves, and hah, those silly historians! And then I will immediately get a headache.

2 Flexible circular knitting needles for knitting tubes are, as you might guess, also a more modern invention. If you’re in the Medieval period, it’s four sticks or bust.

3 My girlfriend and I made a valiant attempt to verify this, including squinting at some scans of fragments from Ancient Greek dictionaries written on papyrus from Papyri.info – which is, by the way, easily one of the most websites of all time. We didn’t make much headway.

The dictionaries or bibliographies we found on papyrus seem to be ordered completely alphabetically, but even those “source texts” were copies from ~1500 CE or that kind of thing, of much older (~200 CE) texts. So those texts we found might have been alphabetized by the copiers. Also, neither of us know Ancient Greek, which did not help matters.

Ultimately, this citation about both primary and secondary alphabetization seems to come from Lloyd W. Daly’s well-regarded 1967 book Contributions to a history of alphabetization in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, which I have not read. If you try digging further, good luck and let me know what you find.