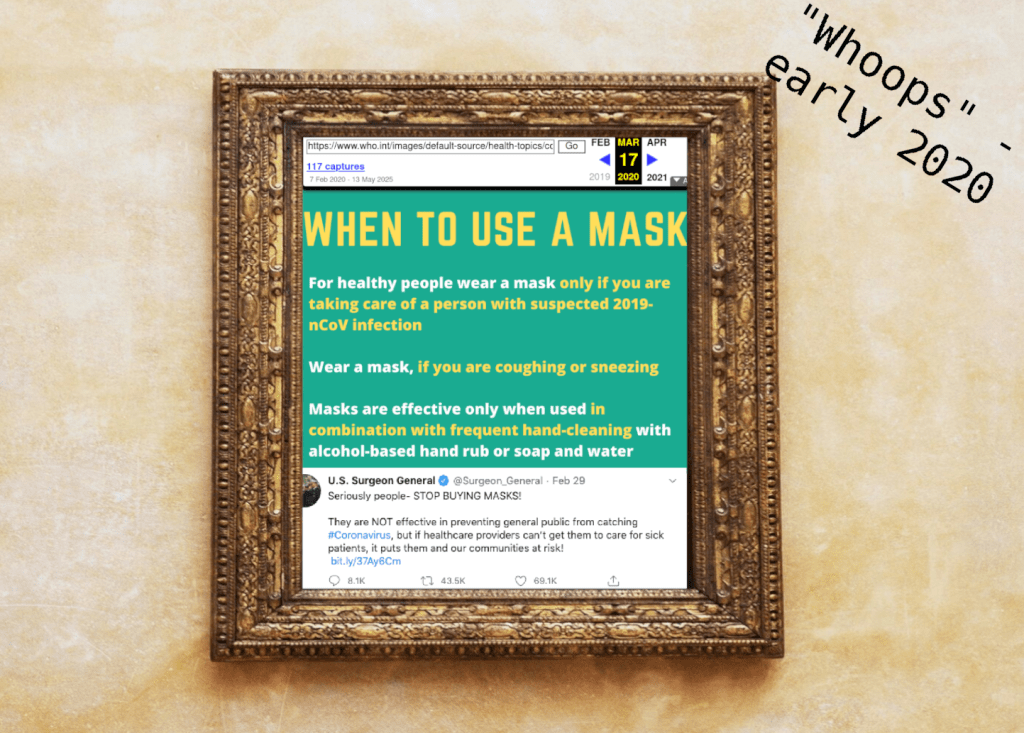

Remember early 2020 and reading news articles and respected sources (the WHO, the CDC, the US surgeon general…) confidently asserting that covid wasn’t airborne and that wearing masks wouldn’t stop you from catching it?

Man, it’s embarrassing to be part of a field of study (biosecurity, in this case) that had such a public moment of unambiguously whiffing it.

I mean, like, on behalf of the field. I’m not actually personally representative of all of biosecurity.

I did finally grudgingly reread my own contribution to the discourse, my March 2020 “hey guys, take Covid seriously” post, because I vaguely remembered that I’d tried to equivocate around face masks and that was really embarrassing – why the hell would masks not help? But upon rereading, mostly I had written about masks being good.

The worst thing I wrote was that I was “confused” about the reported takes on masking – yeah, who wasn’t! People were saying some confusing things about masking.

I mean, to be clear, a lot of what went wrong during covid wasn’t immediately because biosecurity people were wrong: biosecurity experts had been advocating for years for a lot of things that would have helped the covid response (recognition that bad diseases were coming, need for faster approval tracks for pandemic-response countermeasures, need for more surveillance…) And within a couple months, the WHO and the Surgeon General and every other legitimate organization was like “oh wait we were wrong, masks are actually awesome,” which is great.

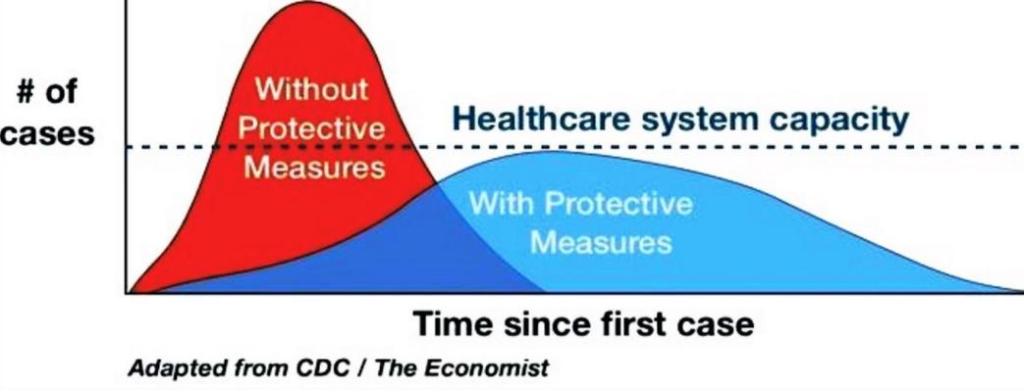

Also, a lot went right – a social distancing campaign, developing and mass-distributing a vaccine faster than any previous vaccine in history – but we really, truly dropped the ball on realizing that COVID was airborne.

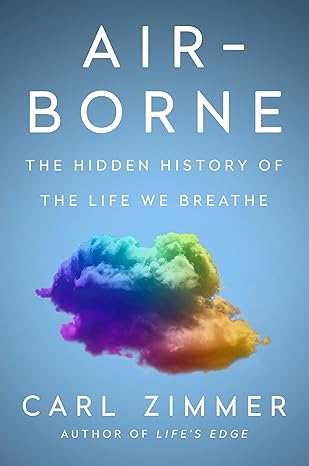

In his new book Air-borne: The hidden history of the air we breathe, science journalist Carl Zimmer does not beat around this point. He discusses the failure of the scientific community and how we got there in careful heartbreaking detail. There’s also a lot I didn’t know about the history of this idea, of diseases transmitting on long distances via the air, and I will share some of it with you now.

Throughout human history, there has been, of course, a great deal about confusion and debate about where infectious diseases came from and how they were spread, both before and to some extent after Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch et al illuminated the nature of germ theory. Germ theory and miasma theory were both beloved titans. Even after Pasteur and Koch had published experiments, the old order, as you may imagine, did not go quietly; there were in fact series of public debates and challenges with prizes and winners that pitted e.g. Pasteur up against old standouts of miasma theory.

One of the reasons that airborne transmission faced the pushback it did is that it was seen as a waffley compromise of a return to miasma theory. What, like both a germ and the air could work together to transmit a disease? Yeah, sure.

Airborne transmission was studied extensively in the 1950s. It eventually became common knowledge that tuberculosis was airborne. That other diseases, like colds and flu and measles, could be airborne, was the subject of intense research by William and Mildred Wells, whose vast body of work included not only proving airborne transmission but experimenting with germ-killing UV lights in schools and hospitals — and who remain virtually unknown to this day.

Let us acknowledge a distinction often made between droplet-borne diseases, where heavy wet particles might fly from a sneeze or cough for some six feet or so, to airborne diseases, which might travel across a room, across a building, wafting about in the air for hours, et cetera. This distinction is regularly stressed in the medical field although it seems to be an artificial dichotomy – spewed particles seem to be on a spectrum of size and the smaller ones fly farther, eventually becoming so small they’re much more susceptible to vagaries in air currents than to gravity’s downward pull. Droplet-borne diseases have been accepted for a long time, but airborne diseases were thought by the modern medical establishment to be very rare.

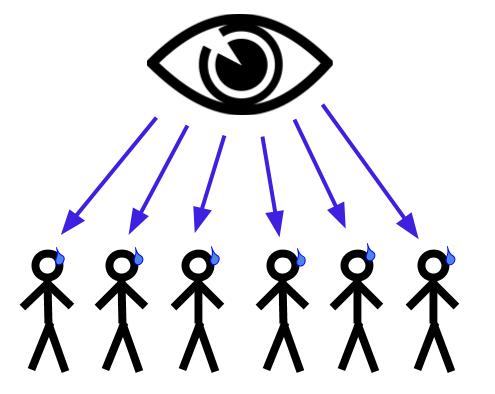

(I forget if Zimmer makes this point, but it’s also easy to imagine how it’d be easier for researchers to notice shorter-distance droplet-borne transmission – the odds a person comes down with a disease relates directly to how many disease particles they’re exposed to, and if you’re standing two feet away from a coughing person, you’ll be exposed to more of the droplets from that blast than if you’re ten feet away. Does that make sense? Here’s a diagram.)

(But that doesn’t mean that ten-foot transmission will never happen. Just that it’s less likely.)

Why didn’t the Wells’ work catch on? Well, it was controversial (see the ‘return to miasma’ point above’), and also, they were just unpleasant and difficult to work with. They were offputting and argumentative. Also Mildred Wells was clearly the research powerhouse and people didn’t want to hire just her, for some reason.* Their colleagues largely didn’t want to hire and fund them or to publish their work. We have a cultural concept of lone genius researchers, but these are, in terms of their impact, often fictional – science is a broadly collaborative affair.

The contrast in e.g. Koch and Pasteur’s status vs. William and Mildred Wells made me think about the nature of scientific fame. I wonder if most generally-famous scientists were famous in their lifetimes too. Koch and Pasteur were. Maybe most famous scientists are also famous because they’re also good science communicators. I’m sure that also interplays with getting your ideas out into the world – if you can write a great journal article that sounds like what you did is a big deal, more people will read it and treat it like a big deal.

The Wells were not a big deal, not in their day nor after. Their work, studying disease and droplet transmission and the possibility of UV lamps for reducing disease transmission (include putting lamps up in hospitals and schools), struggled to find publication and has only recently been unearthed as a matter of serious study.

Far UV lamps are the hot new thing in pandemic and disease response these days. Everyone is talking about them.

There’s variations and nuance, but the usual idea works like this: you put lamps that emit germ-killing UVC light up in indoor spaces where people spend a lot of time. UVC light can causes skin cancer (albeit less than its higher-energy cousin, UVB). But you can just put the lamps in ventilation systems or aimed up at the ceilings, where they don’t point at people or skin but instead kill microbes in the air that wafts by them. Combined with ventilation, you can sterilize a lot of air this way.

William and Mildred Wells found results somewhere in between “positive” and “equivocal” – the affect being stronger when people spent more of their day under the lamps, e.g., pretty good in hospital wards and weaker in schools.

They’re not too expensive and could be pretty helpful, especially if they became de facto in places where people spend a lot of time – and especially in hospitals. Interest in this is increasing but there’s not much in the way of requirements or incentives for any such thing yet.

*Sexism. Obviously the reason is sexism.

The other heroes of the book are the Skagit Valley Chorale. In March 2020 a single Skagit Valley Chorale choir rehearsal transmitted multiple fatal covid cases during a single choir practice. Afterwards, the survivors worked with researchers, who figured out where everyone was standing, where points of contact were, did interviews and mapping and figured that there had been no coughing or sneezing, that the disease had in fact been flung at great distances just by singing – that it was really airborne. (There were other studies in other places indicating the same thing.) But this specific work of contact tracing was a focus and was instrumental and influential, and cooperation between academic researchers and these grieving choir members formed an early, distinct piece of evidence that covid was indeed airborne.

I think being part of research like this – an experimental group, opting into a study – is noble. It’s selfless, and what a heroic and beautiful thing to do with your grief and your suffering, to say: “Learn everything you can from this. Let what happened here be a piece in the answer to it not happening again.”

(Yeah, I got dysentery for research, but listen, nobody in the Skagit Valley Chorale got $4000 for their contributions. They just did it for love. That’s noble.)

There was also a cool thread of the story that involved microbiologists like Fred Meier and their interactions with the early age of aviation – working with Lindbergh and Earhart and balloons and the earliest days of commercial aviation to strap instruments to their crafts and try to capture microbes whizzing by.

And they found them – bacteria, pollen, spores, diseases, algaes, visitors and travellers and tiny creatures that may have lived up their all their lives. Another vast arm of the invisible world of microbes.

I’ve been interested in the mechanics of disease transmission for almost as long as I’ve been interested in disease. In freshman year in college I tried an ambitious if bungled study on cold and flu transmission in campus dorms. (That could have been really cool if I’d known more about epidemiological methods or at least been more creative about interpreting the data, I think. Institutions are famously one of the easier places to study infectious diseases. Alas.) Years later I tried estimating cold and flu transmission in more of an EA QALY/quantifying-lost-work days sense and really slammed into the paucity of transmission studies. And then covid came, and covid is covid – we probably got the best data anyone has ever gotten on transmission of an airborne/dropletborne disease.

More recently, I’ve been doing some interesting research into rates and odds of STD transmission, and there’s a lot more there: there’s a lot of interest and money in STD prevention, and moreover, stigmatized as they are, it’s comparatively easy to determine when certain diseases were caught. They transmit during specific memorable occasions, let’s put it like that.

For common air- or droplet-borne diseases? Actual data is thin on the ground.

I think this is one of the hard things about science, and about reasoning in and out of invisible, abstract worlds – math, statistics, physics at the level of atoms, biology at the level of cells, ecology at the level of populations, et cetera. You know some things about the world without science, like, you don’t need to read a peer-reviewed paper to know that you don’t want to touch puke, and you don’t need to consult with experts in order to cook pasta. The state of ambient knowledge around you takes care of such things.

And then there’s science, and science can tell you a lot of things: like, a virus is made of tiny tiny bricks made of mucus, and your body contains different tiny virus detectors (also themselves made of mucus), and we can find out exactly which mucus-bricks of the virus trigger the mucus-detectors in your body, and then we can like play legos with those bricks and take them off and attach them to other stuff. We know about dinosaurs and planets orbiting other stars.

And science obviously knows and tells us some useful stuff that interacts with our tangible everyday world of things: like, you can graft a pear tree onto a quince tree because they’re related. A barometer lets you predict when it’s going to rain. You can’t let raw meat sit around at room temperature or you might get a disease that makes you very sick. Antibiotics cure infections and radios, like, work.

And then there’s some stuff that’s so clearly at this intersection that you might assume it’s in this domain of science. Like, we know how extremely common diseases transmit, right? Right?

It used to blow my mind that we know enough about blood types to do blood transfusions and yet can’t predict the weather accurately. Now it makes visceral sense to me, because human blood mostly falls into four types relevant to transfusions, and there are about ten million factors that influence the weather. (Including bacteria.)

Disease transmission is a little bit like predicting the weather, because human bodies and environments are huge complicated machines, but also not as complicated, because the answer is knowable – like, you could do tests with a bunch of human subjects and come up with some reasonable odds. We just… haven’t.

Actually, let’s unpack this slightly, because I think it’s easy to assume that airborne (or dropletborne) disease transmission would be dirt cheap and very easy to study experimentally.

To study disease transmission experimentally, you need to consider three things (beyond just finding people willing to get sick):

First, a source of infection. If you’re trying to study a natural route of infection like someone coughing near you, you can’t just stick people with a needle that has the disease – you need a sick person to be coughing. For multiple reasons, studies rarely infect a person on purpose with a disease, let alone two groups of people via different routes (the infection source and the people becoming infected) – you might need to find a volunteer naturally sick with the disease to be Patient Zero.

Second, exposure. People are exposed to all sorts of air all the time. If you go about your everyday life and catch a cold, it’s really hard to know where you got the cold from. You might have a good guess, like if your partner has a cold you can make a solid statistical argument about where you were exposed to the most cold germs – or you might have a suspicion, like someone behind you on the bus coughing – but mostly, you don’t know. A person in a city might be exposed to the germs of hundreds on a daily basis. In a laboratory, you can control for this by keeping people isolated in rooms with individually-filtered air supplies and limited contact with other people.

Third, when a person is exposed to an infectious disease, it takes time to learn if they caught it or not. The organism might get fought off quickly by the body’s defenses. Or the organism might find a safe patch of tissue to nestle in and grow and replicate – the incubation period of the infection. It’ll take time before they show symptoms. Using techniques like detecting the pathogen itself, or detecting an immune response to the pathogen, might shave off time, but not a lot, you still have to wait for the pathogen to build up to a detectable level or for the immune response to kick in. Depending on the disease, they also may have caught a silent asymptomatic infection, which researchers only stand a chance of noticing if they’re testing for the presence of the pathogen (which depending on the pathogen and the tests available for it, might entail an oral or nasal swab, a blood test, feces test…)

So combine these things – you want to test a simple question, like “if Person A who is sick with Disease X coughs ten feet away from Person B, how likely is Person B to get sick?” The absolute best way to get clean and ethically pure data on this is to find a consenting Person A who is sick with the flu, find a consenting Person B (ideally who you are certain is not already sick, perhaps by keeping them in an isolated room with filtered air beforehand for the length of the incubation period), have Person A stand ten feet away and cough, and then sweep Person B into an isolated room with filtered air for the entire plausible incubation period, and then see if they get sick, and then have this sick person cared for until they are no longer infectious.

And then repeat that with as many Persons B as it takes to get good data – and it might be that only, like, 1% of Persons B get sick from a single sick person coughing 10 feet away from them. So then you need, I don’t know, 1000 Persons B at least to get any decent data.

It’s not impossible. It’s completely doable. I merely lay this out so that you can see that producing these kinds of basic numbers about disease transmission would instantly entail a lot more expense and human volunteers than you might think.

A friend of mine did human challenge trials studying flu transmission, and they did it similarly to this – removing the initial waiting period (which is fair, most people are not incubating the flu at any given moment) and with more intense exposure events, with multiple Persons B in a room actively chatting and passing objects around with a single Person A for an hour, and then sending Persons B to a series of hotel rooms for a few days to see if anyone got sick.

(What about going a step further: just having Person A and Persons B in a room, Person A coughs, and then send Persons B home and call them a few days later to ask about symptoms? You could compare this to a baseline of Persons C who were not in a room with a Person A coughing (“C” for “control”). Well, I think this would get you valid and usable numbers, but exposing people to infectious diseases that could then be freely passed on to nonconsenting strangers is considered a “bioethics no-no” – and so researchers have, to my knowledge, mostly not tried this.)

(Maybe someone did that in the sixties. That seems like something they’d have done back then.)

The point is, it’s like, expensive and medium hard to study airborne disease transmission experimentally. Adjust your judgment accordingly.

Anyway, fascinating book about the history of the history of that which you think might be better understood by virtue of being a life-and-death matter millennia old, but which is, alas, not.

Here are some questions I was left with at the end of the book:

- What influences whether pathogens are airborne-transmissible? Does any virus or spore coughed up from the lungs have about the same chance of becoming airborne, or do other properties of the microbe play a role? (I was hoping the book would explain this to me, but I think the research here may not exist.)

- Zimmer is clearly pro-far-UV but the Wells’ findings on far UV lamps in schools was in fact pretty equivocal – do we have reason to think current far UV would fare better? (I know I linked a bunch of write-ups but I’m not actually caught up on the state of the research.)

- Some microbes travel for long distances, hundreds of miles or months, while airborne. Often high in the earth’s atmosphere. How are these microbes not all obliterated by solar UV?

Find and read Air-borne by Carl Zimmer.

Support Eukaryote Writes Blog on Patreon. Sign up for emails for new posts in the blog sidebar.

Crossposted to: [EukaryoteWritesBlog.com – Substack – Lesswrong]