Man, I don’t think so.

Background

The Miracle of the Sun at Fatima was a 1917 event predicted by several children who said they were visited by the Virgin Mary. Thousands of people showed up in the field in Fatima at the predicted date, and witnessed odd celestial phenomena. It was validated by the Catholic Church as a true miracle.

Accounts are not unanimous, but witnesses generally reported the sun as moving around, changing colors, and “spinning” in the sky.

This has a couple interesting features: It was documented at the time and many thousands of people were there, and later gave their eyewitness accounts – and it was photographed by journalist Judah Bento Ruah for the Portuguese newspaper O Século (“The Century”).

The sky does not actually show up in the photos, which is expected – photographing the sun was especially hard in 1917, and Ruah didn’t show up expecting the sun in particular to be doing something weird. (Nor were the pilgrims – they were expecting a miracle, but didn’t know what it would be.) Ruah’s photos, first published soon after the event, sure do show a lot of people gathered in a field, staring rapt at the sky.

Dr. Phillipe Dalleur analyzed these, and wrote a paper (“Fatima Pictures and Testimonials: in-depth Analysis”, Scientia et Fides, September 2021) arguing that these photos indicate that the light source in the photo corresponding to the observed sun is at about 29°, not at the expected solar angle of about 40° – so it’s concrete evidence of a true miracle, right?

More recently, Ethan Muse at Motiva Credibilitatis uses this point to argue the same. Muse and Dalleur points to other aspects of the event too – e.g. even if the apparent odd behavior of the sun was due to really weird meteorological conditions, how were the children apparently able to predict that? What were the people seeing? What were the children reporting?

See e.g. Evan Harkness-Murphy at The Magpie for possible explanations for some of these other attributes that do not require supernatural explanations.

But as a woman with a fondness for A) very concrete claims of unexpected phenomena and B) OSINT, I’m only going to be looking into the angle-of-the-sun thing.

Because I do agree that if these photos showed that the sun was at an odd angle, that would be evidence for a miracle. The photos were first published days after the event, so while there were ways to doctor photos at the time, they would have had to have done it quickly. The photos were taken by a Jewish journalist who did not have a clear motive to fake evidence of a Christian miracle (attributed to the Virgin Mary). Lots of people corroborated the date and approximate time of the event, and the sun is, of course, one of the most reliable physical phenomenon there is. If that can change, maybe it has to be God doing it.

But I read Dalleur (2021) and I’m really not sold that the photos indicate anything celestially weird going on.

Dalleur’s data

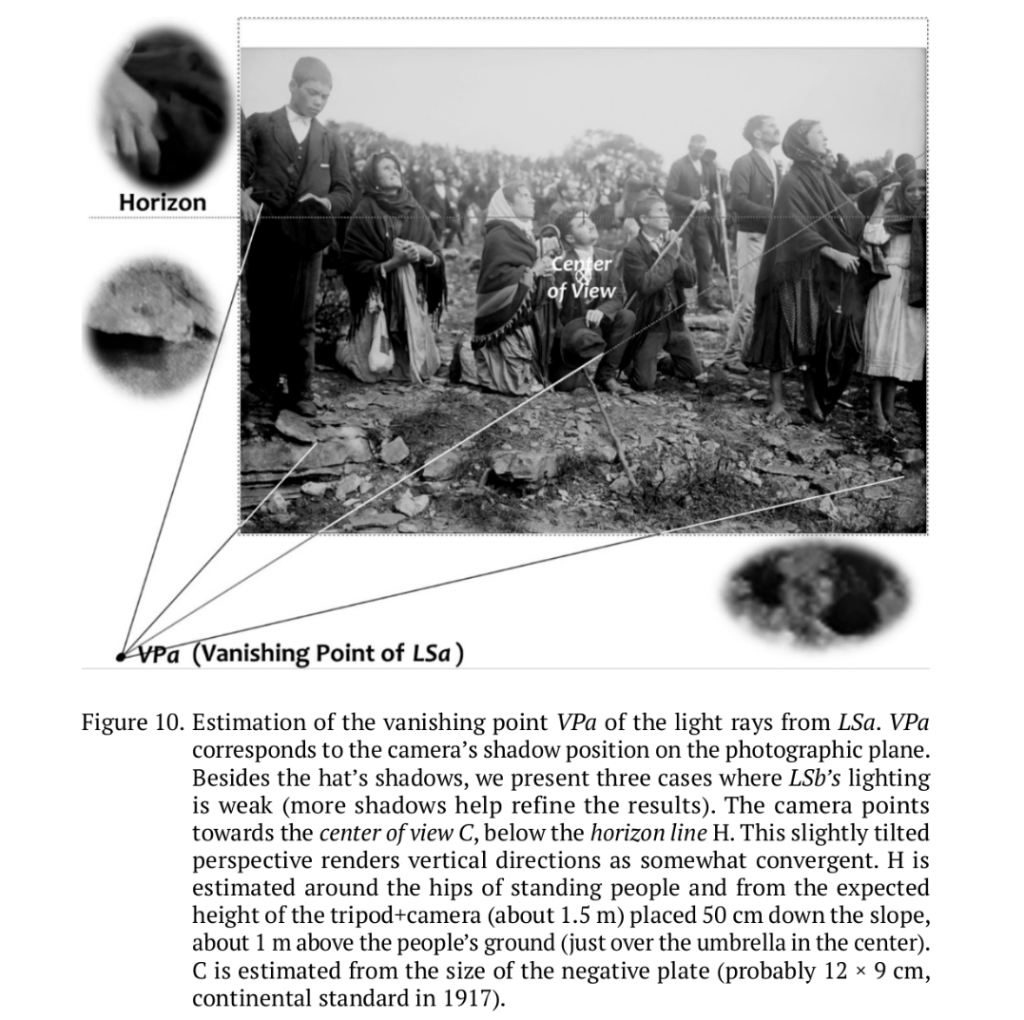

Most of Dalleur’s argument comes from one photo, listed on the Shrine of Fatima website and in his paper as D115. It’s this one – we’ll be referring back to it a lot.

I’m going to ignore the part in Dalleur’s paper about the dry parts on the clothing. I think it’s explainable by conventional means. People don’t necessarily stay at exactly the same angle for long and shift around, and might be uncovering and covering themselves to dry off after being rained on at idiosyncratic angles. I don’t think this tells skeptics much about the light source.

Dalleur has clear photos; we don’t

A lot of Dalleur’s argument has to do with shadows in the photographs. The shadows are really faint, which is what we’d expect – everyone agrees that it had recently stopped raining, so the sky is cloudy and the lighting is diffuse.

The public photos of these photos are low-resolution and do not really show shadows. Dalleur obtained high-quality scans of these photographs from the originals at the Shrine of Fatima. These versions show the detailed shadows Dalleur is using for his analysis, and as far as I can tell, aside from cropped excerpts included in Dalleur’s paper, these higher-resolution versions are not available online.

Compare what sure looks like the shadow of this cane in Dalleur’s version, to the enlarged version of the photo I was able to download from the Shrine of Fatima’s website. You can’t really tell there’s a shadow in the lower-res public version.

More shadows would be really useful for analysis. (I sent Phillipe Dalleur an email asking for the full versions but haven’t heard back yet.) It would be much easier to evaluate his claims if these were available.

On using the sun in OSINT

I went into this hoping that one of the photos had a specific shadow. Nick Waters at Bellingcat outlines how to use shadows for chronolocation – that is, identifying when a photo was taken.

In short, if you have a photo with an object lit by the sun and casting a shadow –

- Where the casting object is roughly vertical

- Where the shadow is cast on level ground

And…

- You know where the photo was taken

- You know what date the photo was taken

- You know vaguely what direction the shadow is pointing

…Then you can tell what time the photo was taken.

If you have other parts of this information, like you do know the time, you can also tell e.g. where the photo was taken, or at least narrow it down to certain parts of the world.

In this case, we know where, when, AND what time the photo was taken – at least roughly. Our question is whether all of this information lines up the way we expect. If the shadow looks different, then the light source must be different, like, say, if the sun or a sun-like object is moving miraculously around the sky.

But alas, there is no shadow in these photos that meets these criteria. This isn’t surprising. Everyone agrees that it was raining shortly beforehand, so the sky was still cloudy and the lighting was diffuse. (Also, again, the publicly available photos are so low-quality you can hardly make out any specific shadows at all.)

All of this is to say that Dalleur has to use much more complicated methods to estimate the sun’s angle, and I see why. There aren’t good shadows for the simpler method described by Waters.

I just don’t think the methods he used instead are good enough to draw the conclusions he draws.

Are there really two light sources?

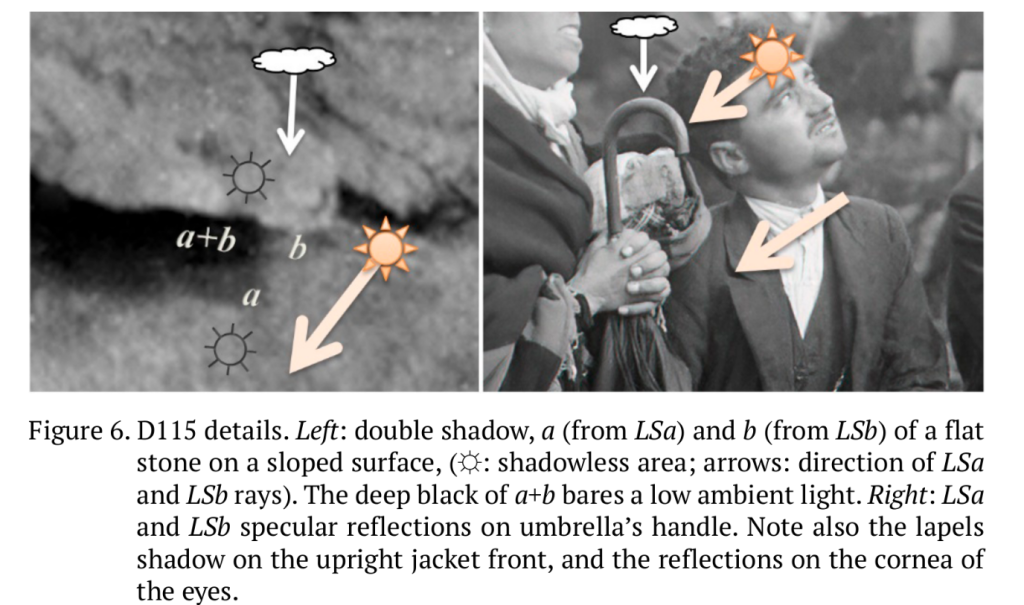

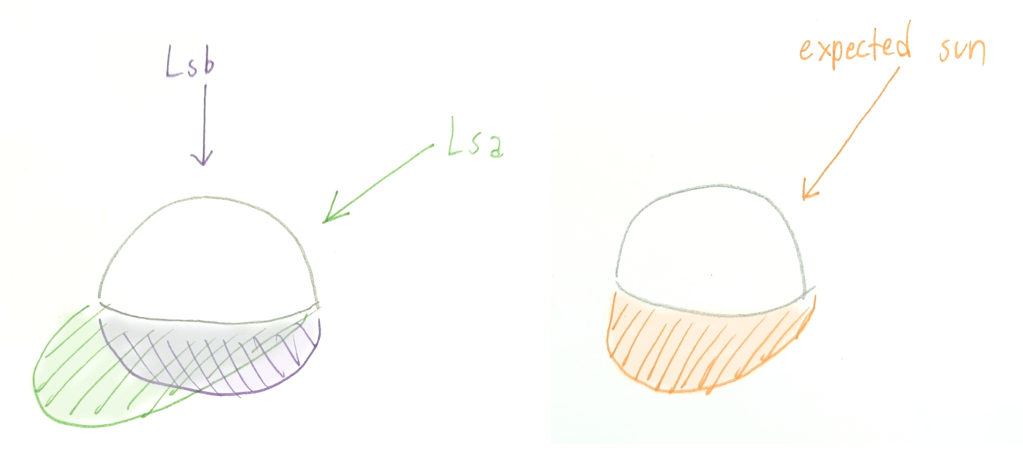

First of all, Dalleur’s argument includes an assumption that there are two light sources casting shadows – the light source corresponding to the thing the witnesses identified as the moving sun (“Light source a” AKA Lsa), plus a diffuse, higher-up light source, probably sunlight bouncing off and/or filtering through a cloud (Lsb).

A quick note – I grew up in Seattle so I’ve experienced plenty of overcast and weirdly-sunny-sort-of-overcast days. I don’t remember seeing a double shadow under these conditions. I can’t rule it out, and of course Dalleur isn’t claiming for certain that Lsa is the sun or works just like the sun, but I wouldn’t go in expecting a double shadow in these conditions.

In any case, Dalleur only points out one example of a double shadow, cast by a rock on rocky ground. (Left, below.) While the excerpt does look like a double shadow, it could also be the shadow of the rock next to it, or the ground color, or water from the rain that hasn’t dried yet.

There’s also an example of the two light sources cast on a curved umbrella handle (right, below), but the “separation” between the two light sources could be a darker part on the wood of the handle.

Like, it’s just the rock. I guess all I’m saying is that if you assumed there was only one shadow cast, and evened out Lsa and Lsb, that would look more like one light source higher in the sky (more like the expected location of the sun.)

I’m unclear to what degree these are explicitly built into the final analysis that gets us to the final 29°-Lsa-angle number. Dalleur looks at 4 shadows and as far as I can tell, only one of them (this rock) features a double shadow.

In any case, Dalleur spends time on the “two light sources casting shadows” thing and I’m not sold based on the example given.

I’m pretty sure there’s too much assumption to make the math reliable

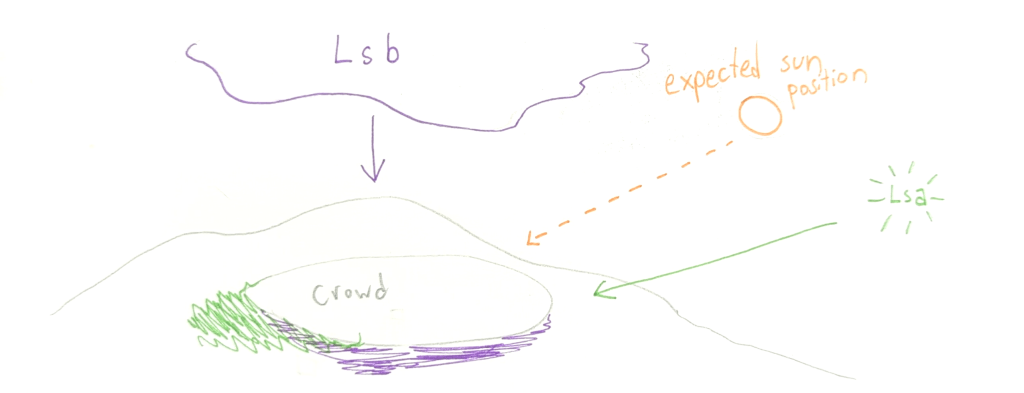

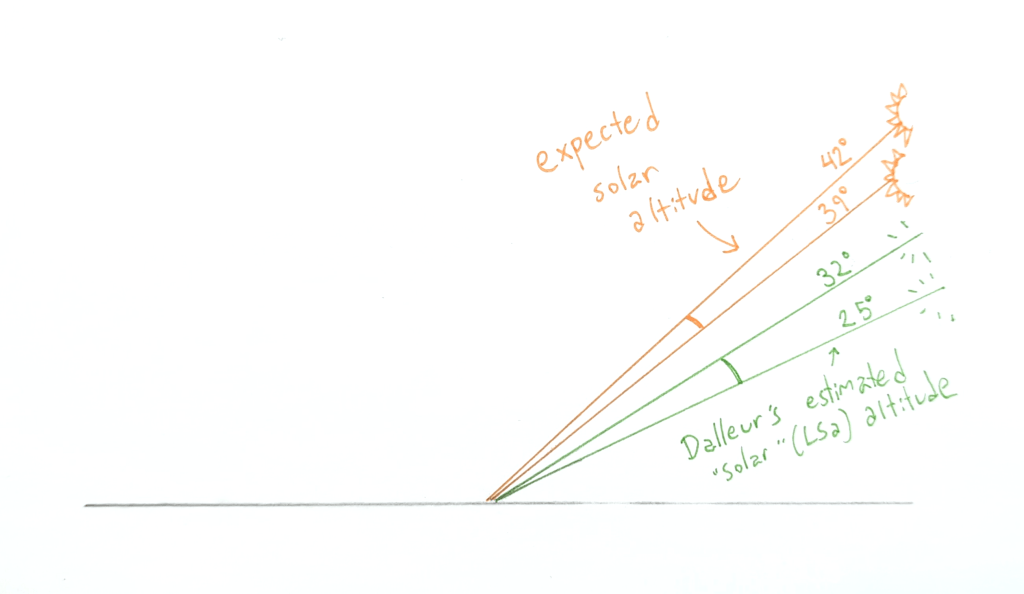

First of all, here’s a (angle-accurate) sketch of the situation in question. According to Dalleur and to live testimony collected by John de Marchi in “The True Story of the Miracle at Fatima”, the miracle takes place for a few minutes somewhere between noon and 1:30 in solar time, Fatima, Portugal, October 13 1917. so according to SunCalc.org, the sun should be at a solar altitude of 39°-42°. Dalleur agrees. He suggests that the apparent “sun” (his Lsa) angle in the photo he analyzes is 25°-32°.

To be clear, if this were true, astronomically, this would be bananas – the sun is so reliable that if we had a good piece of evidence that it had been anything else (say, there were a sundial on level ground in the photo that clearly had an incongruent shadow) we should be very surprised indeed. But I show you this drawing so you get a sense that we’re not dealing with, like, a hugely different angle, especially as estimation error comes into play. Which it will.

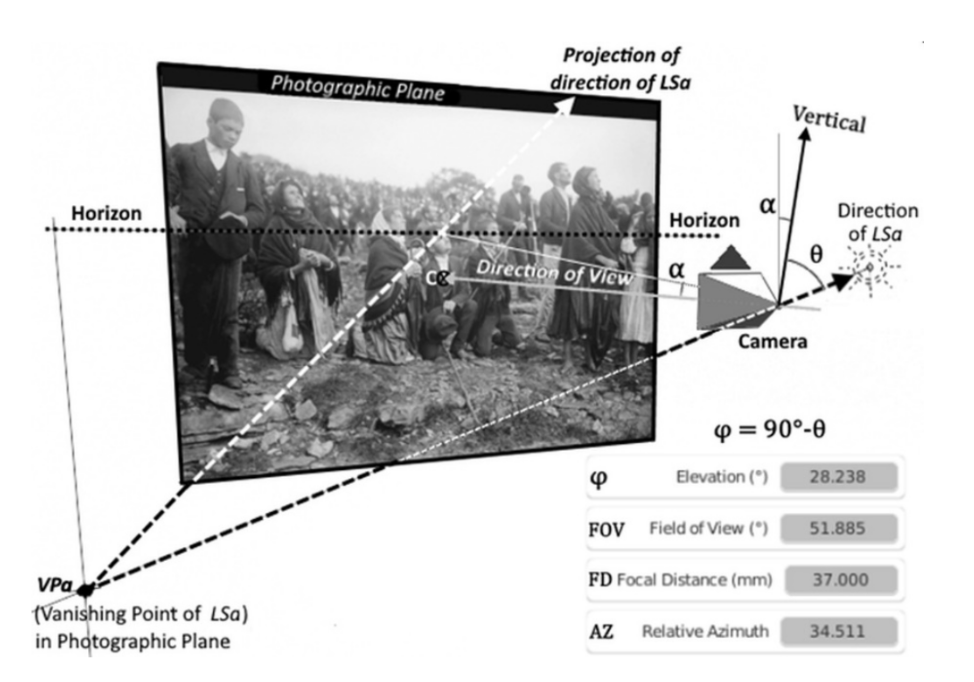

As far as I can tell, the main argument about that 29°-angle comes from photo D115 (the same photo we’ve been looking at so far) and some math about photo optics and what “pitch” and “roll” angles the photo was taken at.

I can’t pretend I totally understand or can replicate the math used. But I can tell there’s a lot of estimation. (See around Figure 10 and 11 in the paper.)

While not every estimate used is spelled out, it looks like Dalleur estimated:

- Where the obscured horizon is

- the height the camera is at

- how far the camera seems to be from the reference points

- hanging thread from some of the clothing in the photo, although we’re not sure what and he acknowledges that some other hanging thread on a different person is at a different angle (because of wind)

- The camera being correctly leveled every time, even though we’re told Ruah was moving the camera and taking pictures at an incredibly fast (for 1917) rate of one per minute

- the slope of the ground

- angles of the 4 shadows indicating the direction of Lsa (more on this soon)

- The focal distance of the camera, which was set manually by the photographer and which is estimated partly by using a reference for what good photography practices at the time were.

Even if the math comes up as putting the sun at a ~29° altitude, I’d be shocked if there’s not enough error in there to account for a possible 8% difference in actual solar/Lsa angle.

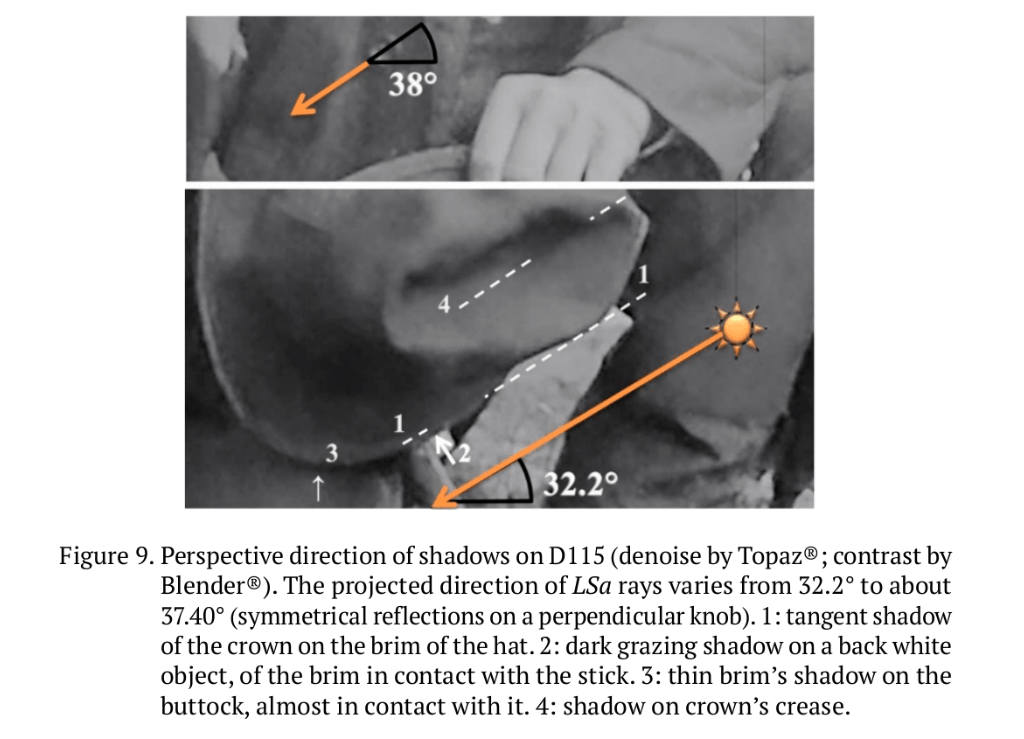

Also, those shadow angles are sus

As best I understand it, the shadow angles are the really important part of this calculation. The whole thing hinges on those angles being unexpected. But we’re looking at total 4 shadows, none of which are cast on level surfaces, and some of which I don’t even think are cleanly cast shadows indicating the direction of Lsa. For 3/4, Dalleur does not indicate what he thinks these angles are.

One of these is the double-shadowed rock from before.

Another (bottom right of the above image) is, apparently, another rock. I don’t even know what precisely I’m looking at here. But it doesn’t look like it’s cast on a level surface. That angle is going to drastically effect what angle the shadow seems to be at.

Another is the hand of the boy on the left side of the photo, and again, I’m not sure what I’m supposed to be gleaning here or what Dalleur thought that angle was. Is it the shadow of the pocket on the thumb? Thumbs are curved! His hand might be angled!

Another is on this hat.

Look at that line 4 on the top of the hat.

To me that could easily be the fold on the “bowl” of the hat, and not something that would tell us much about the specific angle of the light source. And either way, it’s cast on the “bowl” of the hat, which we wouldn’t assume to be flat or level.

I think someone with more patience for trig than me, or better yet, experience with Blender or another 3d modelling software, could take a crack at this more definitively – like, setting up this scenario with some models and playing with the angles and light sources (Blender can definitely simulate one diffuse light source vs. two light sources at different angles, etc) and seeing what looks most like the shadows in the photos. I expect the shadows in the photograph will be totally in line with natural phenomena and the natural position of the sun.

Thanks for reading – this is a post a friend encouraged me to hammer out. I’ll link his related analysis when it’s up. I’ll be back to biosecurity soon, I promise. I have a freaky virus to tell you about and everything.

This post is mirrored to Eukaryote Writes Blog and Substack.

Support Eukaryote Writes Blog on Patreon.

Very thorough, thank you! Coincidentally, I just happened to publish an investigation of my own into an alleged incidence of the Virgin Mary appearing to a believer and issuing prophecies and instructions! In my case, though, there was no such physical evidence as you have to examine — just second- and third-hand allegations in memoirs written decades later.

LikeLike

Although the prediction of the miracle was widely known, especially in Europe and the Vatican, there are no reports of the sun’s behavior anywhere else. Which suggests that the Virgin Mary would have altered a narrow band of light waves and not the sun itself. Still quite miraculous. Nonetheless, an analysis of photographic shadows based on the sun’s normal behavior, serves no purpose if we accept that the phenomena was local. Given the fine tuning of our solar system, if the sun moved or changed positions, the orbits of the planets would fall into chaos.

LikeLike