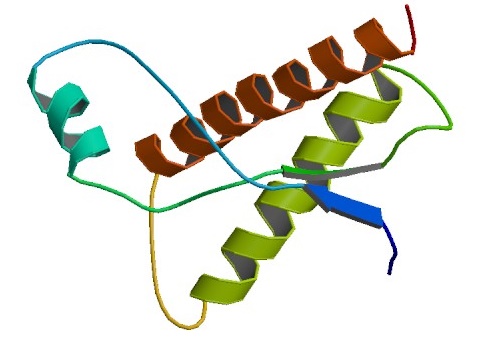

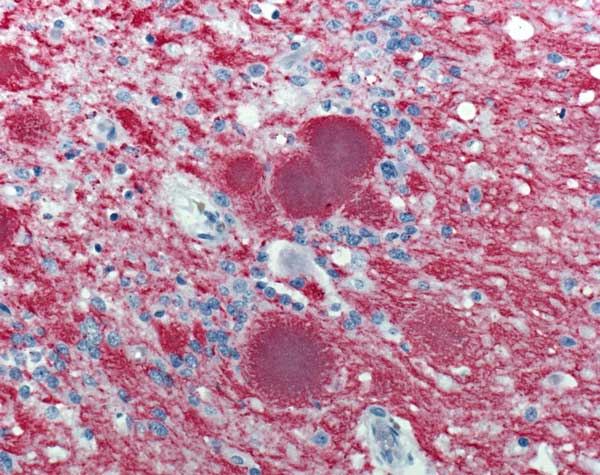

Image: Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) prion.

First of all: It’s usually pronounced “pree-on.” If you say “pry-on”, people will probably still know what you mean.

This is an exploratory post on what prions are, and how they work, and a lot of other things I found interesting about them.

Primer on protein folding

- Proteins are strings of amino acids produced from blueprints in DNA. Proteins run your cells, catalyze reactions, and do just about every important thing in the body.

- A protein’s function is determined from its amino acid composition, and then mostly from its shape. A protein’s shape determines what other kind of molecules it can interact with, how it’ll interact with them, and everything it can do. One of the main reasons amino acid composition is important is because it determines how proteins can fold.

- One string of amino acids can be folded into different shapes, which will have different properties. (The particular shape of a specific string of amino acids is called an isoform.)

- While strings of amino acids will fold themselves into some kind of shape as they’re being made, they may also be folded later – into different or more complex shapes – elsewhere in the cell.

- One of the things that can refold proteins is other proteins.

- A prion is a protein that folds other, similar proteins into copies of itself. These new copies are very stable and difficult to unfold.

- These copies can then go on and fold more proteins into more copies.

CJD’s impact in the brain – red clumps are amyloid plaques, surrounded by blue clumps of prion proteins. || Image is public domain by the CDC.

Some prion diseases

Prion diseases in animals appear to be mostly neurological. All known mammal prions are isoforms of a single nerve protein, PrP. They can both emerge on their own when the protein misfolds in the brain, or spread as an infectious agent.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease affects one in one million people. (It’s also the most common modern prion disease. Prion diseases are very rare.) It comes in a variety of forms, but all have similar symptoms: depression, fatigue, dementia, hallucinations, loss of coordination, and other neurological symptoms, generally resulting in deaths a few months after symptoms start.

- 84-90% of cases are sporadic, meaning that the protein misfolds on its own. This mostly occurs in people older than 60.

- 10-15% of cases are familial, where a family carriers a gene that makes PrP likely to misfold.

- >1% of cases are iatrogenic, meaning they occur as a result of hospital treatment. If medical care fucks up really badly, they might transplant organs from people with CJD, or inject people with growth hormone extracted from the pituitary glands of dead people, or even just use surgical tools once on CJD patients, and they catch it.

(The surgical tools one is really scary. Normal autoclaves – that operate well above the threshold needed to inactivate bacteria and viruses – kill some but not all prions. And while it takes a large dose of ingested prions before you’re likely to get sick, it takes 100,000 times less when exposure is brain-to-brain. Cleaning with “benzene, alcohol and formaldehyde” still doesn’t kill prions. The World Health Organization issued prion-specific instrument cleaning procedures in 1999- towards the end of Britain’s brush with bovine spongiform encephalopathy- which include bleach or sodium hydroxide and longer autoclaving. I don’t know if these are still used outside of known epidemics.)

Mad cow disease, or bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), is also a prion disease. It transmitted between cows when they were fed a feed that contained meat and bone meal, including brain matter from cows with the disease. The incubation period is between 5 and 40 years. The source molecule is essentially a cow-originated Creutzfeld-Jakob prion, and when the prion replicates in humans, it’s probably the cause of variant Creutzfeld-Jakob disease.

Between 1900 and 1960, the Fore people of New Guinea had an epidemic of an unknown neurodegenerative disease – mostly among women – that caused shaking, difficulty walking, loss of muscle coordination, outbursts of laughter and depression, neurological degeneration, and eventually death.

The Fore tribe practiced funerary cannibalism, and women both prepared and ate the dead, including the brains, and fed them to children and the elderly. This transmitted kuru, a prion disease with an incubation period of years. The last known sufferer of kuru died in 2005.

(The source of kuru was probably a single person with CJD. There are other tribes that practiced funerary cannibalism– I wonder if any of them also had prion epidemics from eating the brains of people who spontaneously developed CJD.)

Fatal familial insomnia is a genetic prion disease. Unlike CJD or BSE, fatal familial insomnia prions target the thalamus. If your family has it, and you inherit it, you live until about 30 – then lose the ability to sleep, hallucinate, and die within months. There is no cure. There are more painful and equally fatal diseases, but this must be one of the scariest.

Undulates really get the short end of the prion stick. Chronic wasting disease affects elk and deer and can run rampant in herds. Scrapie affects sheep and goats, and makes them scrape their fleece off and then die.

Prion evolution

Prions differ from their pathogenic, self-replicating brethren – the viruses, the bacteria, the parasites – in one major way: They don’t have DNA or RNA. They don’t even have a central means of storing information.

But studies show that prions can evolve. They can’t change their amino acid composition because they’re not involved in producing it, but do change their progeny’s folding.

This doesn’t seem surprising. The criteria for something to undergo Darwinian evolution don’t necessarily require DNA – just a self-replicator that has some level of random variation, and passes that variation down to its replicas.

Most brain prions don’t transmit, though, so it seems safe to say that the evolutionary lineages of most prions are very short – less than the lifespan of the host. Very contagious prions, like scrapies, presumably have jumped from host to host many times and have longer lineages.

Structure of death

All known mammal prions are variants of a single gene, PrP, and exist in the brain. Why?

Some hypotheses:

- Brain proteins are more likely to misfold than other proteins

- Why? Brain proteins replicate less than other proteins, and are really really central to the body’s function.

- PrP is especially liable to turn into a self-replicator if misfolded.

- Predictions: Other amyloid-based brain diseases are also PrP isoforms. Prions have a similar shape that makes replication happen. Maybe PrP itself self-replicates in the body under some circumstances.

- The brain clears misfolded proteins less well than other body parts.

- Predictions: Other waste product buildup happens in the brain. The rest of the body has some way of combating amyloids or prions.

We know of very few prions (we know that one non-mammal animal, the ostrich, may have them.) Except in fungi. Fungi have tons of prions. Fungi prions don’t come from the same gene either – if you click through to that last link, you’ll see that the misfolds came from a variety of initial proteins that don’t appear to be related at all. Presumably, they have widely different structures.

So why are these the two prion hotbeds? Here’s what I suspect.

We know that both fungi and mammal proteins have related structures – they’re amyloids, aggregating proteins with a distinctive architecture called a cross-β-sheet. (Amyloids in general are implicated in some other diseases, and are sometimes produced intentionally as well. Spider silk has amyloids.) Beta sheets are long, sticky amino acid chains that attach to each other, forming large, water-insoluble clumps that are difficult for the body to clear.

To take an ad hoc survey that could loosely be called a literature review, let’s take the Wikipedia page for amyloid-based diseases. Of those listed, four involve deposits in the brain, and four form deposits in the kidneys (runners-up include ones that deposit in a variety of organs, and ones that deposit in the eyes.

Why the kidney? Given its role as the body’s filter, it makes sense: if a protein floats in the blood, it’ll end up in the kidney, and if multiple sticky proteins circulate, they’ll end congregate there. Wikipedia points out that people on long-term dialysis are also more likely to develop amyloidosis.

Why the brain?

The blood-brain barrier limits the reach of the immune system into the brain, where it could potentially deal with amyloids that it recognizes as foreign material. Sequestered beyond the reach of the immune system, the brain and nervous system clear loose gunk and proteins (including amyloids) via the glymphatic system, via channels in the brain called astrocytes. (The glymphatic system appears to do much of its work while you’re asleep.)

[Caution: Speculation.] I suspect that this system has a lower flow-through rate than the circulatory or lymphatic system, which are responsible for the same task on the other side of the blood-brain barrier. Fungi, including yeast, don’t seem to have robust waste-clearing systems. This might be the connection that explains how prions build up in each.

What about other multicellular organisms without circulatory systems- do prions exist for bacteria, plants, or larger fungi? I don’t think we know. I’m guessing that they exist in other animals or organisms, but since they’re made up of the same compounds as the rest of the body, it’s very difficult to find or test for a prion – if you’re not sure what you’re looking for. [/speculation]

Drawing blood to test a sheep for genetic resistance to scrapie. || Public domain, by USDA Agricultural Research Service.

Some notes on infectivity

- Scrapie is transmitted between sheep by cuts and ingestion, and chronic wasting disease is often transmitted by ingestion, as when a sick deer dies on ground that grows grass, which is eaten by new herbivores. They can also be aerosolized (yikes).

- CJD and kuru are still infectious, but less so- you have to ingest brain matter to get them.

- Meanwhile, Alzheimer’s disease might be slightly infectious- if you take brain extracts from people who died of Alzheimer’s, and inject them into monkey’s brains, the monkeys develop spongy brain tissue that suggests that the prions are replicating. This technically suggests that the Alzheimer’s amyloids are infectious, even if that would never happen in nature.

What makes scrapie so much more transmissible than CJD, and CJD so much more transmissible than Alzheimer’s? I’m not sure. The shape of the prion might be relevant. Scrapie is just another mutation of PrP, so I’m not sure why no human prions have ever had the same effect (except that since scrapie is a better replicator, it would only need to have happened once in sheep.)

It might also be behavioral – sheep appear to shed scrapie in feces, and undulates have more indirect contact with their own feces than other animals (deer poop on grass, deer eat the grass, repeat.)

Fun Prion Facts

- We can design synthetic prions. Current synthetic prions are also variations of the PrP protein in mammals.

- Did I mention they can be airborne? They can also be airborne.

- Even though they’re just different configurations of proteins that are already in your body, the immune system can distinguish prions from normal proteins. For a while we thought this was a problem because most immune cells can’t cross the blood-brain barrier, but it turns out some can.

- The possibility of bloodborne prion transmission (of mad cow disease) is the reason why people who lived in Britain during certain years still can’t donate blood in the US.

- Some fungi also appear to produce a molecule that degrades mammal prions. Don’t take that at face value – as far as I could tell, the study didn’t compare non-prion PrP to prion PrP. That said, it has implications for, say, treating surgical instruments.

- The zombie virus isn’t real, but if it were, it would definitely be a prion and not a virus.

- Sometimes, if you’re infected with one prion, it’s more difficult for you to get infected with another. This is true sometimes but not always.

- Build-up of amyloids or prions may sequester pathogens in the brain.

- Finally, for most diseases, if we eliminated all of the extant disease-causing particles, the disease would go extinct- the same way that if we kill off of species X and don’t store its DNA, species X goes extinct forever and never comes back. Creutzfeldt-Jacob is an interesting case of an infectious self-replicator where that isn’t true. Even if all CJD prions were instantly destroyed, it would emerge naturally in the genetic or spontaneous cases where the brain itself misfolds proteins, and could spread iatrogenically or through ingestion.