If you live in this one tiny county in California, you might be more likely to die from Sin Nombre Virus than in a car crash.

In the same way that “why does the frozen spinach I want to buy cost much more than it used to?” engages with a vast interconnected web of economies and monetary policies and farmers and supply chains, asking “what’s up with this rare disease people sometimes get in my part of the world?” is actually a question about the entire ecosystem, plus how organisms even work.

The reason you have to think about the natural world when you do biosecurity is that the vast majority of human diseases come from animals. What we think of as diseases to humans is a two-dimensional slice of a giant, rotating, obscure shape of many dimensions – a whole world of diseases, little communities of microbes and macrobes interacting and evolving and getting sick and occasionally passing their diseases around between them. Communities of parasites built on communities of hosts, all colliding constantly. This is the large scale of biosecurity. Nothing in infectious disease research makes sense without it. Any question about human health or symptomology or individual risk or what have you is a tiny speck on the shore of this ocean.

Occasionally, one of those parasites reaches out of the host community it’s adapted to, and finds a foothold in another host. And so the sphere gets a little bigger, a little more interconnected.

Today we’ll be looking at a single slice of the grand pageant, about this size – one virus in one part of the world, that sometimes slips from its home and finds its way into a human animal.

Sin Nombre Virus

Sin Nombre Virus was first characterized in 1993 in New Mexico. Since then, there haven’t been many identified infections, but every now and then, cases crop up. Even in the medically well-equipped United States, Sin Nombre virus has maintained an astonishing 40% mortality rate.

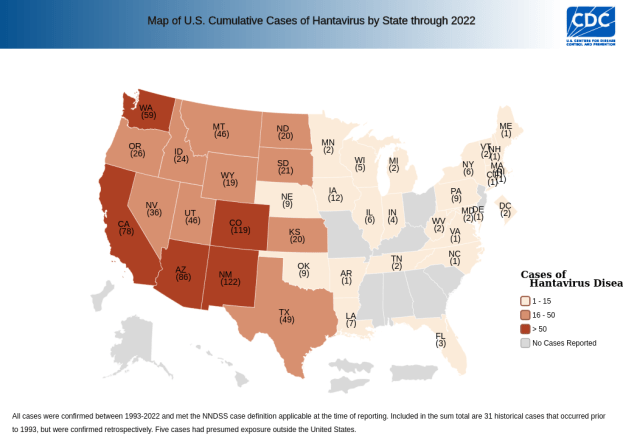

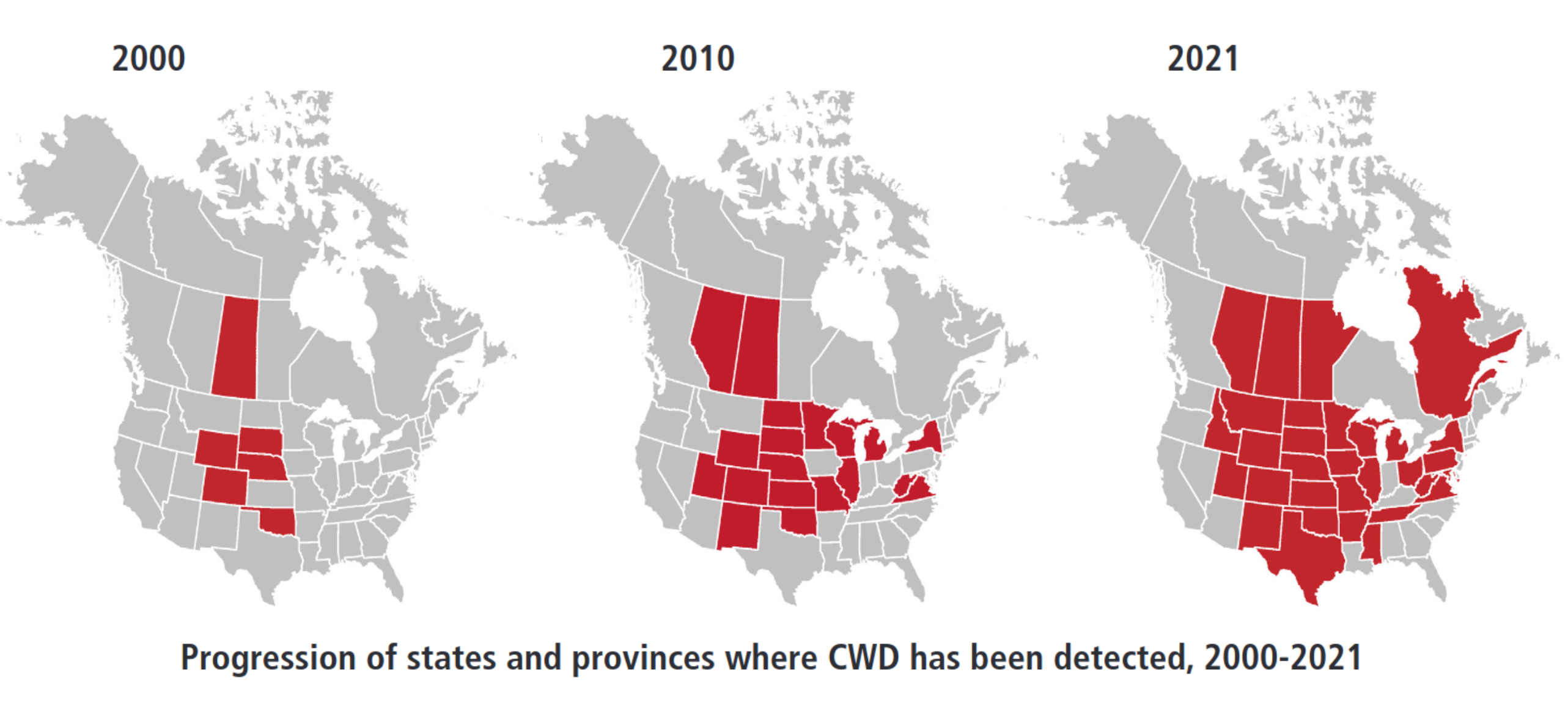

Here’s a map of hantavirus infections in the US by state, since its discovery. We can see that it’s far-reaching, but it clearly has a geographic localization.

So if you live in California, your risk is even comparatively low. But out of curiosity, let’s look closer at a map of SNV infections in California counties.

Huh, what’s the deal with that one county? Note that this is a total case map, not a per capita case map, and that county doesn’t have any large cities. In fact, it’s the 4th least populated out of California’s 58 counties. So the risk is even higher than that map makes it look!

But it’s pretty unlikely that any given blogger would live in that county, isn’t it?

Ha ha, what a funny idea. Anyway, I happened to take an interest in this rare, hyperdeadly disease.

The virus without a name

Most current reporting describes the disease we’re looking at today with the more general name of hantavirus – which it is, but there are multiple human diseases in the hantavirus family.

They’re split into the Old World and New World hantavirus. The Old World hantaviruses cause hantavirus hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS) in Eurasia.

The New World hantaviruses include our subject of interest today as well as the related Andes virus in South America (plus a few other, even rarer North American viruses we’ll discuss later). Andes virus has similar symptoms and is about as deadly as Sin Nombre Virus, but it sees more cases every year – 100-200 versus North America’s “dozens” – and it shows occasional person-to-person spread. We’ll come back to that, but for now, I’m focusing on the most common North American hantavirus because it’s the one that’s in my own backyard. …Potentially literally.

The North American hantavirus we’re discussing today is more specifically known as Sin Nombre virus. Why is it called that?

It was discovered in 1994 after a lot of people got sick in the Four Corners region of New Mexico. Local Native communities actually had stories about odd numbers of people getting suddenly sick and dying during years where the pine nut harvest was good, and indeed, 1994 was a good pine nut mast year. Because of abundant nuts to eat, the mouse population exploded and came into a lot of contact with humans, and enough people got sick and died that USAMRIID and the CDC investigated. And they found a virus at the root.

Ongoing practice at the time was to name newly-discovered viruses after geographic locations nearby the site of origin. But this was already facing pushback – who wants to take a vacation to the scenic Ebola River? On top of that, the area and early cases were heavily Native American communities, and before the disease was shown to NOT be communicable, Native groups were facing racism and shunning over this mystery disease.

The Four Corners region didn’t want it to be the Four Corners virus; the nearby Muetro Canyon was proposed but rejected because the Navajo community didn’t want more stigma (and also Muerto Canyon was named after a massacre against the Navajo), and back and forth, and eventually they just called it the virus without a name, AKA Sin Nombre virus.

I have some thoughts on infectious disease naming that are too long for the current margin to contain, but I will say that I think this is the kind of cool infectious disease naming schema that you can pull off once.

Mice

This is the western deer mouse, Peromyscus sonoriensis. Sin Nombre virus lives here.

This is a pretty common strategy of infectious viruses – playing the slow, long game. Humans have a few: cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus (especially HSV-1), Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1… viruses that lots of people have for their entire lives, and have no idea that they have.

Compare also things like the common cold or human papillomaviruses that cause warts – shorter lifespan and some chance of symptoms but also not much, really. The immune system eventually clears these out in most cases without help, but they have time and means to spread, and they circulate among us and periodically annoy us, but mostly, they don’t kill us.

The deer mouse is not the same thing as the house mouse Mus musculus, which you’re probably more familiar with. But let’s take a minute here.

There’s mice and then there’s mice

We all know Mus musculus – it’s the common house mouse, which has spread worldwide alongside people. If humans build a town, the house mouse will soon follow. There are a lot of less-common related species of mice, like the adorable African pygmy mouse (Mus minutoides).

We also know the common brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) and black rat (rattus rattus). They’re two related species that have also spread nearly worldwide, and love to hang out with humans.

But Peromyscus sonoriensis isn’t either of these. Technically speaking, is it a rat or a mouse?

Well, what a great question. It’s neither.

Huh, you might think. Mice are on there twice? If you know your way around a phylogenetic tree, you may wonder: maybe the common ancestor was more like a mouse, and it’s rats that are doing something weird?

Ha. Haha. Hahahaha. No. The real situation is more complicated than you could possibly believe.

Rats and mice have evolved multiple times, with some incredibly weird variations in the mean time.

This is the distance between the western deer mouse and the house mouse:

Different genes, same niche

Despite all of this genetic distance, hice mice and deer mice occupy extremely similar niches. Where the western deer mouse is native, it’s completely comfortable cozying up to human dwellings and making its nests inside our big, fancy, warm, dry, food-filled nests.

And deer mice that are widely regarded as the vectors of Sin Nombre virus – the host species that it’s evolved to circulate in. In New Mexico, two studies (one statewide, one in an area where a human was infected) found that about 35% of deer mice had the virus at any given time. Eyeballing it, this lines up pretty well with a “disease circulating stably among the mouse population that rarely spontaneously spills into humans” situation.

…But wait, are deer mice really the only carriers? That second study also found replicating, viable Sin Nombre virus in other local rodents – including the house mouse, mus musculus! The sample sizes weren’t huge, but 3 out of the 9 captured had it!

Note, however, that they only found house mice at one of the sites. There were many more deer mice than house mice. But still, 3/9!

What I don’t know, and what I don’t think anyone knows, is the degree to which hantavirus actively circulates among these other rodents. Are they just getting it incidentally from neighboring deer mice, or do they pass the virus around between themselves too? Is Sin Nombre virus just as at home in them as it is in western deer mice?

The literature is very clear that deer mice are the ones associated with Sin Nombre virus infection. For instance:

The most common hantavirus that causes HPS [that virus being SNV] in the U.S. is spread by the deer mouse.

CDC

But “common house mice (Mus musculus), which are prevalent in urban and suburban communities, do not carry hantavirus,” said Charles Chiu, MD, PhD, professor of laboratory medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of California, San Francisco.

2025 MSN article

(Sidenote: this article also quotes one of those New Mexico survey articles I mentioned above, saying that it “found less than 9% of deer mice had the virus.” The study did report that 10/113 deer mice had antibodies to SNV, but it also found that 37/113 of the deer mice had SNV DNA in their system. This is weird, because viral DNA is a sign of an active infection – it’s made by a virus! – but the immune response can linger for a long time after infection, so we’d really expect more mice to have antibodies to SNV than to have SNV DNA. The study does mention that this trend held up across all rodents studied, so maybe this just has to do with the sensitivity of their antibody assay.)

And there are a lot of cases where people got sick, in which the victims knew they’d come into contact with material contaminated by deer mice.

But there are also cases of infection where nobody saw a mouse, and the presence of any mice at all just has to be intuited. Is it possible that Mus musculus is responsible for some Sin Nombre cases in humans?

The public health literature is pretty unanimous about the deer mouse thing, so I’m going to proceed assuming that’s effectively the only way any human gets Sin Nombre virus, but I don’t understand why they’ve ruled out other mice too.

Human

The adventures of a dead-end host

Sin Nombre virus is a transient inside human beings – it’s not adapted here, it doesn’t stay here. We know this because when we isolate the virus from infected humans, it doesn’t easily reinfect deer mice. This suggests that small mutations have to occur to make the virus able to replicate in humans – ones that make it less viable within mice.

[…] which implies that humans are truly dead-end hosts of SNV. Thus, virus evolution is primarily, if not exclusively, occurring in the natural rodent reservoirs.

Prévost et al, 2025

But SNV can infect humans, and a virus has to replicate to make its host sick. How does it do that?

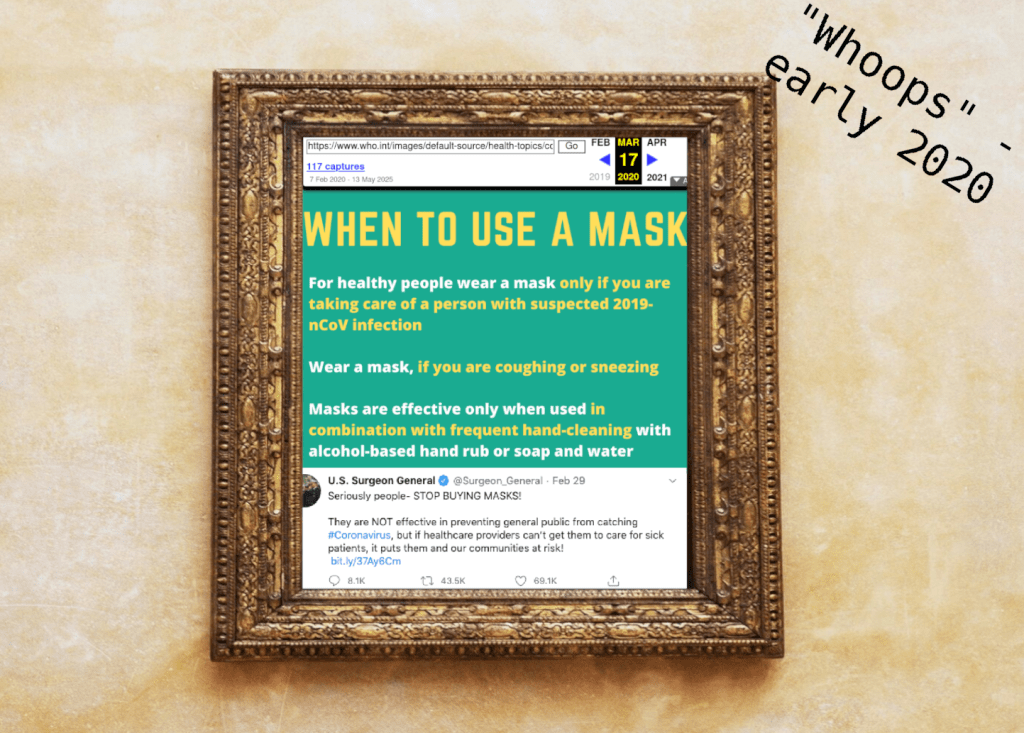

Well, it’s almost always inhaled from mouse-contaminated material. Then the virus somehow gets into the blood stream.

Once it’s there, Sin Nombre virus replicates inside a variety of human cells, but especially likes endothelial cells and macrophages.

Endothelial cells are the guys that line our blood vessels. They grow everywhere the blood vessels grow, which is to say, all over

Macrophages are a kind of immune cell that devours pathogens. The SNVs are captured by the macrophages, and as with all of their prey, are moved into a lysosome – a cellular chamber that turns into an acid bath, designed to inactivate complex biomolecules (and pathogens they’re attached to) trapped within. But the SNV particles escape into the cell membrane just as the acidification starts.

Replicating inside immune cells is a pretty common strategy for viruses. Sure, the immune cells try to spot and destroy pathogens, but they also end up capturing and moving pathogens around a lot, which can be a big boon if the pathogen has a way to just not get killed by the cell.

Some macrophages roam the bloodstream, but others are concentrated in outposts around the body. Some are in the lungs.

As far as I can tell, Sin Nombre Virus probably gets into the lungs, then infects the alveolar macrophages (and possibly other lung-based immune cells), and then escapes from those into the blood stream where it might infect other endothelial cells. They might also manage to get through tears or thin spots in the alveolar-capillary membrane and get straight into the blood – that’s just a guess.

Replicating in endothelial cells seems kind of overpowered for a virus, right? Like, we have a gazillion of ‘em and they’re all over the body and once you’re next to the bloodstream, it’s an easy highway for a virus to get from one part of the body to a totally different part of the body. to spread from one part of the body to a totally different part of the body – and if you mounted an inflammation or severe immune response, that seems like that would kill the entire host easily and quickly.

And indeed, Sin Nombre Virus does kill its host quite effectively. Ebola, another famously lethal disease, also replicates in endothelial cells. Covid seems to be able to sometimes (in addition to its main habitat in the respiratory tract, an interesting similarity between it and Sin Nombre Virus.)

So is replication in endothelial cells a sure sign that a disease will wreck havoc on the human body?

Well, no. Dengue fever replicates in endothelial cells, and most of its hosts are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic. Its fatality rate is literally one in a million. And moreover, cytomegalovirus is an endothelial replicator. Like we talked about before, cytomegalovirus of those viruses that’s almost a commensal – most people have symptomless cytomegalovirus infections. (It can cause disease in unborn fetuses, infants, and the immunocompromised, and seems to contribute to cancer risks down the line – it’s not great – but, again, most people have it.)

Also, lots of viruses attack tissues that are essential and would be bad to call the full attention of the immune system to – herpes viruses (another near-commensal genre of virus that most infected carry without any symptoms whatsoever) infect nerve cells, for instance. Lots of viruses infect the lungs, which are famously important, and some of them kill you and some of them are no big deal.

So I think a general lesson here is that the driver of virulence here has more to do with the rate of growth / level of viruses active at once and the degree to which they activate the immune system, not the infected tissue.

Do a bunch of people within the regions where it is have indications of asymptomatic or past infections?

This is a great question. After all, mice have it quietly, and people seem to have the capacity to carry or fight off a lot of infections quietly without notable symptoms. Are we sure this isn’t the case for hantavirus?

Well, so far as I know, nobody has checked.

Wait, can we talk about the actual disease?

Yeah, fine I guess.

According to the CDC, the early symptoms of Sin Nombre virus disease in humans – AKA hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) or hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS) – emerge 1-8 weeks after acquiring the virus. They start out, like a lot of fucked up viral diseases, with generic symptoms:

- Muscle aches

- Fever and chills

- Malaise

- Headaches

- Abdominal pain

Though “aches” might be a standout. University of Colorado Health (Colorado has a lot of SNV cases) reports that severe muscle aches, especially in the back and lower extremities, are a common hallmark of HCPS cases. (Hey, I got severe leg pain when I got shigellosis on purpose too – shigellosis, much like Sin Nombre virus, is an infectious disease that notably does not target the legs. What’s up with that?)

4-10 days after this, the cardiopulmonary stage of disease begins, AKA “the part that kills you”:

- Coughing

- Shortness of breath

- Fluid buildup in lungs/chest

- Tachycardia

- Arrythmia

- Cardogenic shock

- Respiratory failure

HCPS has a 40% death rate. Deaths occur 24-48 hours after the start of the cardiopulmonary phase. There is no vaccine or known effective antiviral.

Buying time

If you get HCPS and reach the cardiopulmonary stage, the thing that will save your life is a medical technology called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). An ECMO device draws large volumes of blood out of the body via inserted tubes (called cannulae), runs the blood through an artificial lung (called a membrane oxygenator) to remove carbon dioxide and reoxygenate the blood cells, and puts the blood back in the body.

HCPS seems to be one of those diseases where the body can rally and fight off the disease, if it has enough time. I attended an online lecture delivered by clinician Dr. Greg Mertz and this is the sense I got: SNV doesn’t permanently damage the heart and lungs, it just overwhelms them. If ECMO takes over while the heart and lungs are out of commission and keeps plenty of oxygenated blood in the system, the immune system can finish the job and the heart and lungs can go back to work afterward.

If you go to a hospital with symptoms and they make a presumptive diagnosis of HCPS, you can opt into having the ECMO cannulae inserted in advance – they won’t start ECMO until you go into shock (because your heart/lungs fail), but if you do go into shock, they’ll be able to start re-oxygenating your blood immediately. At this point, doing this changes your odds of survival from 50% to 80%.

(I see that in my notes from that talk, I also wrote “Do not go into shock”, as it leads to “DEATH V FAST.” So if you get to decide at some point whether or not to go into cardiac shock in general, try not to.)

So if you think you’ve been exposed to SNV and 1-9 weeks later you start experiencing arrhythmia and shortness of breath, proceed straight to a hospital with an ECMO device.

ECMO devices are not extremely common. You can find out which hospitals near you have ECMO devices on the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization website. If you happen to be reading in Mono County, your nearest ECMO is probably in Reno Renown Regional Medical Center.

Do you need to worry?

Do you actually need to know this? Well, every year in the US, about 15 people die from being struck by lightning, and about 8 people die from hantavirus, so if you’re not in a hantavirus hotbed, almost certainly not.

…But if you’re one of the 12,000 residents of Mono County, then yeah, probably. Mono County has had an unusually high 3 HCPS deaths from hantavirus this year, so you have a 0.025% chance of dying from HCPS.

You might actually be more likely to die from hantavirus as in a car crash (0.012% chance in any given year.)

(Sidenote: Naively, I’d expect Mono County residents to have a 0.000004% of dying by being struck by lightning like anyone else, but if you actually look into it, Florida specifically and the southeast generally have a really disproportionate number of lightning strike deaths. We should probably stop rhetorically treating getting struck by lightning as an entirely random act of god and start thinking of it as a physical event with contributing factors like everything else.)

Questions

Why is the geographic range of hantavirus infection so limited?

Western deer mice cover live in the west half of North America.

Let’s go back to that map of USA state-level infections.

So mostly, that makes sense. But how are there ANY cases in the east half of the state?

SNV’s weird siblings

Those other HCPS cases on the east coast? Well, they’re not (or at least, not only) people who happened to travel from the West Coast, and they’re not (or at least, not only) far-ranging western deer mice.

Those are the work of other, rarer hantaviruses, carried by other rodents, spilling over occasionally into other humans in the same way, causing HCPS, and with about the same fatality rate.

These diseases include:

- Bayou Virus in Louisiana, carried by the marsh rice rat (Oryzomys palustris)

- Monongahela Virus in Pennsylvania, carried by the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus)

- New York virus in Long Island, New York, carried by the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus)

- Black Creek Canal virus in Florida, carried by the Hispid cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus)

Each of these is really rare, even rarer than SNV. But that’s odd in and of itself, right? Like, do all of these host species just interact less often with humans than deer mice in the Western US? Are the viruses less common in their hosts, or even less transmissible than SNV? The answers might be out there, but I don’t know that they are.

I ’m also curious about the California county-level breakdown: why Mono County? (And note that this is raw cases, not cases per capita – Mono County has a tiny population.) Is it because there are more deer mice? Or is hantavirus localized to certain populations of deer mice?

Well, here’s this other data on seroprevalance of hantavirus among captured mice in various counties. Sure enough, Mono County has the highest seroprevalance, at 31%, but apparently 25% of tested mice in Santa Barbara County also had SNV, and Santa Barbara has a lot of people in it!

So why does Santa Barbara see very few human cases, while Mono County has a lot?

Here’s my guess at why: it has to do with the houses, and it has to do with mice. Mono County has a lot of barns, sheds, and vacation houses that are left empty part of the year. The classic situation where a person gets SNV is cleaning out a shed or outbuilding that’s been inhabited by mice, kicking up a lot of mousy dust and particles, and inhaling SNV. A shed or a building that’s left for the summer or winter is a nicer place to build a shelter than under a bush, but it’s still not that cozy – it might not have food inside so the mouse still has to forage a lot, and it might get very cold or very dry. There might not be many other buildings nearby. A region-adapted, mostly-wild deer mouse, is going to have a better go in an outbuilding then the urban Mus musculus – and indeed, every mouse I’ve seen or caught around my home has been a deer mouse.

Santa Barbara County is much more urban and has a warmer climate. I bet the mice that people encounter there are almost all Mus musculus. I bet all the Santa Barbara deer mice live in the wild, outcompeted in cities by the larger and more urbanized mus musculus.

And the deer mice are god’s chosen carriers of SNV, and the Mus musculus aren’t. It’s just a deer mouse disease. So it’s much more likely to crop up where people interact with deer mice, and they do so a lot more in these rural, more-wild environments.

It’s an apparent puzzle that makes a lot of sense once you just ignore the human health angle for a second. SNV is a deer mouse disease that circulates among deer mice. Think about which mice want to live where. Humans, as is often the case, are providers and users of nests, and otherwise, are only relevant incidentally.

But wait, can we check this?

If my model is correct, areas that have high SNV caseloads will:

- Be mostly rural (probably without major cities?)

- Have extreme climates

- Have a lot of outbuildings, plus homes that are inhabited seasonally

It would also be interesting if they’re clearly geographically clustered – like if specifically one part of the world is a hantavirus hotbed.

Yeah, let’s look at some other states that get a lot of SNV cases. I don’t expect to get great data at anything lower than the county level. Colorado and New Mexico both get more SNV cases than California, and have county level data.

I tried to look into this further, and ran into kind of a dead end. Or maybe I’m just wrong.

The counties with the highest rates include La Plata and Weld counties in Colorado, and Mckinley county in New Mexico, which is such a standout that it dwarfs the others.

La Plata County has a population of 55,638 with the largest city (Durango) at 10,000. It has some parks and overlaps a national forest, no major ski areas.

Weld County has several cities and a population of 329,000. (It contains parts of some large cities that are on the border so it’s hard to break down for sure, but a lot of people live here.) Okay, not looking great. It’s fairly flat with some mountains, and mostly farming country.

Mckinley county has one city of 20,000 and no other cities, but a lot of smaller towns and census-designated places and such. Its total population is 73,000, which is pretty big! I can’t find indications that it has a lot in the way of seasonal dwellings – there aren’t many ski resorts. The county does seem to be pretty dispersed, housingwise, which might imply more outbuildings.

So, uh, none of this actually cleanly supports my mode, but it’s not necessarily evidence against it either. We might just need data on which kinds of mice are common in human dwellings in these areas, and how common mice are overall.

What makes Andes virus infectious interpersonally, and SNV not?

It seems like ANDV builds up in the salivary glands of humans, and saliva is its mode of transmission. SNV doesn’t do that.

SNV collects in the lungs and heart. ANDV collects in the heart, lungs, and salivary glands, and tests studies have indicated virus in fluids from both of these. It seems to spread via saliva, droplets, and aerosols. Sex and close contact are major risk factors. Otherwise, ANDV has a similar features and fatality rate to SNV.

Saliva also seems to be how deer mice spread SNV and ANDV among each other – both of them show up in the salivary glands of their host mice, but only ANDV inhabits human salivary glands.

(If we could somehow prove that ANDV could spread from the lungs, well, that would suggest some new mechanism also in play – but that seems hard to test, given that the mouth is, you know, between the lungs and the rest of the world.)

That said, I actually don’t understand why ANDV isn’t airborne, or otherwise transmitted from the lungs. The mousy particles that infect humans seem to be from kicked up dust and such, so there’s reason to think it could be aerosolized – maybe the virus particles don’t escape the lungs very well?

That’s all the things I know about Sin Nombre virus, plus some things I don’t. Let me know if you have the answers. In the mean time, don’t die of cardiopulmonary shock. I, for one, am doing my best out here.

This post is mirrored to Eukaryote Writes Blog, Substack, and Lesswrong.

Support Eukaryote Writes Blog on Patreon.