[Content warning: Moralizing about what food you should eat, descriptions of bad things happening to animals, eating bugs. Also, lots of people can’t go vegetarian or significantly alter their diet at all due to health, cost, time, sensory issues, strong preferences, lack of options, inability to pick your own diet, etc. Most of the ‘alternatives’ posed here take money, time, or majorly changing your habits. If reading this post is likely to make you feel guilty or bad in an unproductive way, feel free to skip it.]

This is a rather utilitarian list of approaches to improving the lives of animals even if you still eat meat. I’ll start with some general strategies, ranked roughly in order from “least to most weird”. See what works with your diet, resources, and preferences.

Basic ideas:

- Eat less meat in general.

- Eat less chicken, eggs, beef, and farmed fish.

- For other animal products, eat Animal Welfare Approved, Certified Humane, or 100% Grass-Fed meat, or buy from a source where you know how the animals are treated.

- Eat species that suffer less, either in farms or at all.

- Pay other people to go vegan for you.

- Support animal welfare by donating money effectively.

I suspect that some people will object to the notion that it’s ever alright to kill or use an animal, and that encouraging people to do this in a “less bad” way is just making compromises with the devil. (As opposed to veganism, which is merely selling your soul to Seitan.) If you’re one of these people, you’re probably already a vegan and this essay isn’t for you.

Not that I entirely disagree- many more people should be vegetarian. That’s not the point, though. Many people are Vegetarian Sympathizers, as I once was. As a young person, for instance, I knew that I had moral issues with the idea of eating animals- that a cow’s brain wasn’t very different from a cat’s, which also wasn’t very different from a human’s. I also knew that meat had unfortunate impacts on the environment and that global warming was a serious problem. But my developmental environment had lots of meat. And also, I had a very strong objection- cheeseburgers.

Pictured: The Seattle restaurant that was the source of my conflict. The mind is willing, but the flesh is weak. | By Jmabel (CC BY-SA)

This wasn’t a rational objection. But we’re not rational creatures, and the Cheeseburger Objection was the actual thing standing in between me and vegetarianism. And if I’m going to eat cheeseburgers anyways, why not eat steak, chicken, fish, etc.?

Honestly, the Cheeseburger Objection is a pretty good one. One cow makes a lot of cheeseburgers. One cheeseburger might make you very happy. Acknowledging that isn’t a reason to stop caring about animal welfare entirely. And Cheeseburger Objectionists can still make extremely meaningful contributions to animal welfare without depriving themselves of that cheesey goodness.

1. Only go vegetarian sometimes.

Meatless Mondays are a thing- don’t eat meat just one day a week. That’s 1/7 fewer animals you’re eating, and gaining valuable practice in cooking and eating vegetarian. If that’s too easy, up it to two days a week. Repeat.

Some other strategies that have worked for people: eat vegan before 5 o’clock (IE, meals before dinner), only eat meat outside the house, only eat meat inside the house.

Or, if you’re inclined towards vegetarianism- except for cheeseburgers- (or orange chicken, shrimp, your uncle’s venison, baseball stadium hotdogs, etc.-) consider just being a Cheeseburger Vegetarian. I think there’s this tendency to think that if you’re not doing something 100% all the way and identify as that, any tendency you have towards it doesn’t count at all. But that’s completely untrue. Given that we live in a world where most people do eat meat, conspicuously eating less meat both saves animals, and is a talking point that puts vegetarianism on people’s radars.

(Of course, if you’re being a Cheeseburger Vegetarian and hoping to talk to other people about it, people might take you less seriously. This might be a problem. You could either keep your cheeseburger habit private and secretive, hoarding McDonald’s in the dark like the world’s most gluttonous dragon – or you could acknowledge that if someone’s going think that plant-based diets are a joke and not important, they can already find whatever reason they want to do that.)

If you don’t know how to cook food or eat meals without meat, maybe the problem is educational. Look for recipes that contain tofu, beans, lentils, TVP, or vegetables. If you only know one kind of cuisine, broaden your horizons- Indian, Ethiopian, Mexican, Chinese, etcetera, all have lots of opportunities for low meat dishes.

We live in a golden age of easily available recipes. PETA, Vegetarian Times, and Leanne Brown’s free cookbooks are a few good resources. Google it. Also, if you want to make a favorite Food X vegan or vegetarian, look up “Vegan Food X” and you will instantly get 4,000 hits including step-by-step photographs and people’s life stories as told through salad dressing recipes. The internet is a magical place.

2. Eat humanely sourced meat.

This is way harder than it sounds. The good news is that meat is given labels which reflect how it was raised. The bad news is that some of these labels are regulated, and some aren’t, and it’s difficult to determine which labels actually correspond to good living environments and which are symbolic or easily falsified.

Look for the following words on packages:

Certified Organic animals may still be subject to a variety of inhumane conditions. The label means that hormones, antibiotics, and some other treatments are not allowed, and that the animal must be allowed to “exhibit natural behaviors.” I suspect that organic animals are somewhat harder to mistreat, because farmers are incentivized to raise animals in low-disease environments, so organic may be better than conventional if those are your only two options. *

Animal Welfare Approved is an independently-verified certification that has very high welfare standards, including for slaughter. Certified Humane is a less strong but similar certification. There are probably other good ones- look for what they require and how they’ve verified.

Hoofed animals: Look for 100% Grass-Fed, a legally-defined term in which all animals must be raised entirely on pasture (grass, etc) and not fed harvested grain. It seems much harder to mistreat a cow raised this way, since it can’t be confined. This is different from grass-finished, pastured, or normal grass-fed, since all cows eat some grass before they arrive at feedlots.

3. Be careful with chicken.

Chickens are extremely common and live extremely bad lives in factory farms, probably moreso than any other animal.

Cage-free or free-range eggs are better than alternatives, but I don’t think they’re humane. A cage-free chicken may have a somewhat better and more natural life than a non-caged chicken, though they’re newly at risk of fighting with other chickens, which caged chickens aren’t. They may still be subject to having their beaks cut off, slaughter of male chicks (half of all egg-laying chickens are killed shortly after hatching), bird flu, crowded environments, being raised in darkness, starvation-based forced molting, etc.

A couple examples:

- Free-range – the amount of time or space required for “outdoor access” isn’t legally defined, and varies from facility to facility.

- A cage-free chicken is still raised in barns or warehouses. They may have no outdoor access, or have their beaks cut or burned off without anesthesia.

- Organic eggs still aren’t treated with antibiotics but can still be raised in factory farms.

- More info on labels.

Putting a picture of happy chickens here seemed disingenuous, so here’s some eggs, I guess. | The Home Front In Britain, 1935-1945.

Any given egg source may well not do some or all of these- for instance, I’ve heard that there are some egg producers that don’t slaughter male chicks, and the cost of raising them is passed to the consumer as a higher price. The key here is to do your research. If you buy based on label X or Y without further investigation, even at a “nice” natural foods store or co-op, your chicken will probably have been raised in painful, inhumane conditions.

I think your best chance at getting humanely raised chickens or eggs is to buy from a home farmer or very small permaculture farm, ideally where you can see the chickens. These are likely to be significantly more expensive than other options. Farms may still slaughter male chicks.

4. Eat species that suffer less.

Quantification of animal suffering is a new field, and practices for calculating it are general estimates. That said, its numbers come from easily understandable ideas- that it’s worse to be a factory-farmed chicken than a feedlot cow, for instance. Some other ideas include that being killed is painful, so an animal that produces more food over a long period means less suffering per food unit (assuming said animal’s day-to-day existence isn’t terrible.) Also, that having a more complex brain probably means you can suffer more. It’s not an exact science, but it’s what we’ve got.

Brian Tomasik, who has studied animal suffering extensively, suggests using this metric that by eliminating chicken, chicken products, and farmed fish from your diet, you reduce the suffering you inflict on animals by an enormous amount.

Clams and mussels have very simple nervous systems and probably do not feel much pain, while full of nutrients comparable to other animal foods. Ozymandias at Thing of Things suggests that eating bivalves and dairy, and otherwise being vegan, can be a good trade-off between health, enjoyment, and helping animals. Also, you still get to eat clam chowder (if it doesn’t have bacon.)

The jury is still out on whether insects experience suffering. On one hand, insects are pretty simple critters; on the other hand, to produce any significant amount of food, you need a lot of insects, so however much moral weight they do have gets multiplied by a lot. On the third hand, about a quintillion die every year, so your own contribution is pretty marginal. (That number is extrapolation- I suspect most insects live less than a year, so the number is probably higher.)

What is known is that insects are nutritious and environmentally friendly. Sourcing insects is difficult and pricey, so try raising your own.

Exotic meats. I suspect that exotic meats (deer/venison, buffalo, ostrich, etc.) are more likely to be raised in more ethical environments, because as species they’re less domesticated, and therefore harder to mistreat as in a factory farm. However, I have no evidence for this.

5. Eat environmentally sound meat.

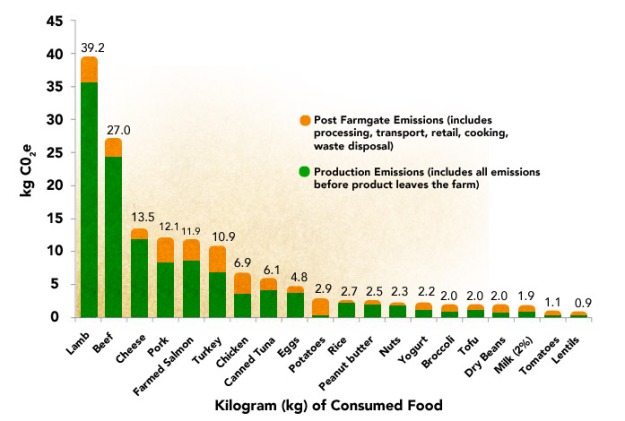

Most of this list comes from a moral argument, but the negative environmental impacts of standard meat is so well-established that it’s worth discussing. 30% of the world’s non-frozen dry land is currently devoted to feeding or raising animals, and 18% of human-produced greenhouse gases came from agriculture. Lamb and beef have disproportionately high greenhouse gas emissions. You’ll note that chicken is rather low on this ranking, but as in the above section, there are other reasons to avoid it.

“Don’t non-animal-product foods also have carbon emissions?” Not that much.

Fish is extremely nutritious, but many species are overfished. Eat conscientiously to avoid making the problem worse- the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch has detailed recommendations for the consumer based on your location, sorted into handy “okay to eat” and “avoid this” categories. Bycatch ratios are another thing to beware: shrimp fisheries are the worst, trawling up an average 6 times more non-shrimp than shrimp.

6. Convince someone else to go vegan.

A review (again by Tomasik) of organizations that run ads promoting vegetarianism suggest that the cost of converting a someone to be vegan for a year is, conservatively, about $100. Do you have the money to spare, and think there should be more vegans, but eating meat is worth more than a hundred dollars to you?

Utilitarianism: it works.

Utilitarianism: It’s this cool. And the ends justify the memes.

This approach won’t work forever, of course – if everybody decided that they individually would eat meat but convince others not to, the cost of getting anyone to go vegan would skyrocket. But not everybody is, and for the time, it’s still low-hanging fruit.

7. Donate to effective charities.

Can we do even better? The average vegetarian saves ~25 land animals per year (and perhaps 371-582 animals per year including fish and shellfish) according to the blog Counting Animals.

The Effective Altruism movement, which is near and dear to my heart, has produced several lovely projects, including Animal Charity Evaluators– a highly evidence-based group that researches which animal welfare organizations have the most bang for your buck. (Sort of the Givewell of the greater biosphere.) An $100 donation to any of their top three charities is estimated to indirectly save or spare the lives of 7,597 animals. (Via outreach, undercover video filming, corporate outreach, and more.)

A final note: People sometimes get annoyed at vegetarians or vegans because they think they’re being smug or morally uppity. This always seemed to me like a strange criticism – the problem is that they’re doing something good? – but if you think it has merit, imagine how smug you can feel in the knowledge that every year, you donate $100 to a certain charity, and that has the same effects as going vegetarian for thirteen years, every year.**

Updated 4/14/2017.

Further reading:

- The Compassionate Carnivore

- The Omnivore’s Dilemna

- The Humaneitarian movement

- Counting Animals

- Brian Tomasik’s writing

* Michael Pollen says in his book The Omnivore’s Dilemna that it’s difficult to get Organic certification, which has many requirements and regulatory steps, so some small and comparatively extremely humane farms may not (despite meeting many or all criteria for the certificate.)

**Note that you’re not allowed to use this to smugly dismiss vegetarianism unless you have actually made a substantial donation to ACE charities. If you don’t, and proceed to use the fact that that someone could make such a donation to be a dick to vegans, you’re doing negative good and the Utilitarianism Skeleton will get you.