Art has died and been reborn a thousand times now. Join me at its graveside once again. Let us speak a few words for what once was. Let us imagine the inconceivable and hollow future ahead without it. If you weep, I will pass you my handkerchief. And let us all pretend to be surprised once more when it bursts out of its coffin, on fire, and singing.

Do you know what song it sings this time? I think you do.

Skibidi Toilet is a wildly popular animated video series. Particularly, it is popular among the youth. Most millennials-and-above I’ve talked to go glass-eyed when its name is invoked. Their souls momentarily leave their bodies, but float back down again in short order. “Why?” they ask, laughing. “Why would you watch that?”

And it’s not completely naive. There’s always been vapid absurd art popular among kids, and wise adults remember and know this. On the internet, it’s stick figure fights and zombocom. Saladfingers and Badger Badger Mushroom. Baby Shark and those weird Spiderman Finger Family Dancing Elsa Learn Colors videos.

Skibidi Toilet is different from all of those. Skibidi Toilet is, like, actually okay.

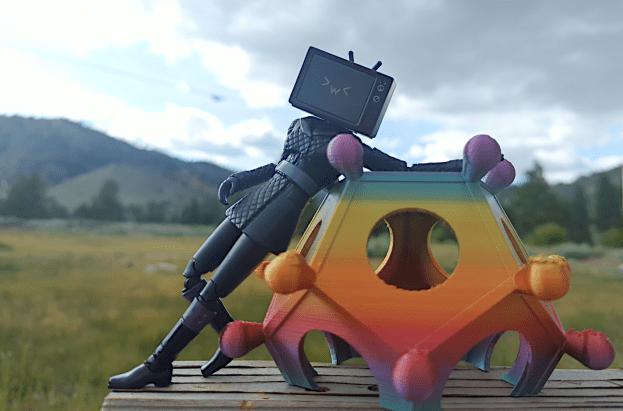

At time of writing, the series stands at 26 seasons and 78 total episodes – but most of the episodes are under a minute long, so it’s only 2.5 hours total. Created by DaFuq!?Boom!, AKA Alexey Gerasimov, Skibidi Toilet is a serial narrative about the unfolding conflict between two groups: the Skibidi Toilets, which are human heads that come out of toilets, and what I think of as the AV Army – humanoid figures with cameras, speakers, televisions, and so on for heads.

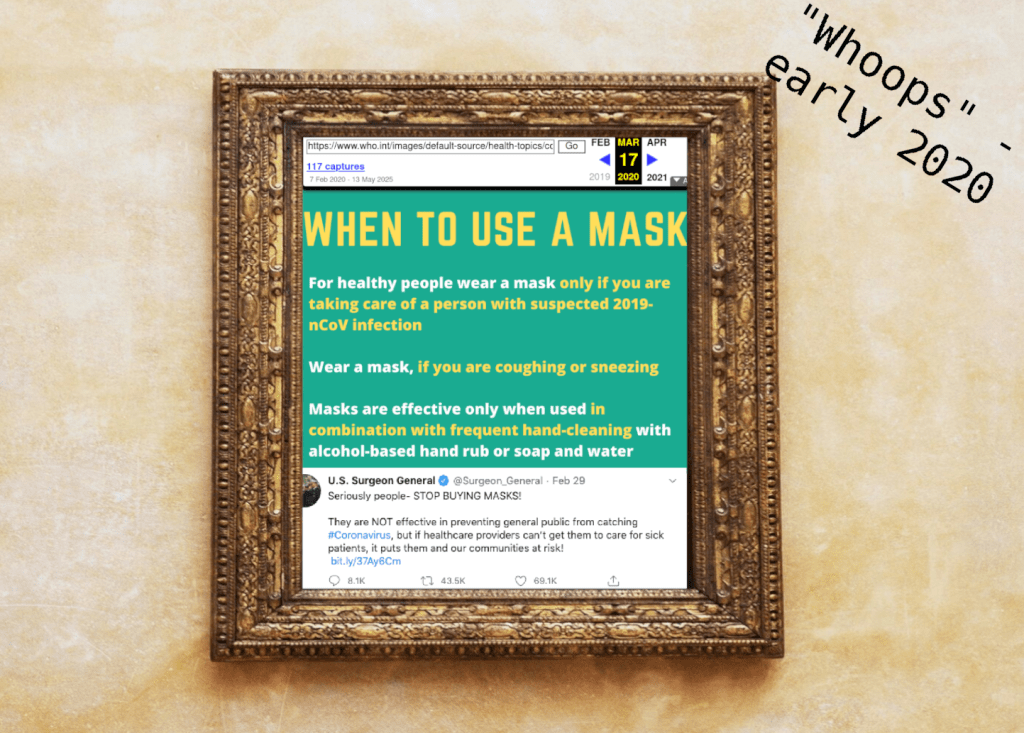

The AV Army is completely nonverbal. The Skibidi Toilets sing, but only the one song, incessantly. There is extremely little verbal or written language throughout the series. Even “skibidi” is a nonsense scat word. (It’s been speculated that this has to do with why the show has been so popular with children, and with international audiences. Is that true? I don’t know, maybe.)

Yes, obviously the toilets can move. You cannot even begin to fathom what these toilets are capable of.

Looking at Skibidi Toilet for the first time, you might think it was made in a janky 3D engine. And you’re partially right. What you might not realize is that it’s made in Source Filmmaker, a 3D engine developed by Valve in 2012 to make animations with video game assets. You might not realize that the series is littered with video game assets and models from games like Half Life and Counter-Strike, and that it was inspired by animations done with Garry’s Mod.

Source Filmmaker is the logical extension of machinima, e.g., movies shot in video games. While Source Filmmaker is definitively a piece of animation software that happens to run on game assets, machinima even in “real” games is a rich genre. Consider Emesis Blue, a psychological action thriller made and set in the world of Team Fortress 2; Whitepine, a sensitive and artistic period drama/mystery made in Minecraft; and of course, the award-winning documentary Grand Theft Hamlet.

Historically, these all stem from an interesting question: Why would you want to watch someone else play a video game?

A brief history of machinima

This makes more sense then you might think. I think for a lot of us, our first memories of video games were watching someone else play it. Friends. An older sibling. Waiting for your turn on the controller, or handing over the reins to your sibling to see if they can do the hard part for you, or just watching.

It’s oddly enchanting to watch someone else play: you get to see the visuals. If there’s a story, you still get to experience the story. If they’re good at the game, it becomes like watching sport. Earliest preserved game footage – not games, videos of people playing games preserved for reasons other than technical demos of the game itself – are of PVP combat or speedruns, i.e., skill.

But even decades ago, people became interested in games as artistic medium. Telling stories about things that might have happened in the game, but then really getting wacky with it, just using the game as artistic expression.

I think it’s interesting to note different levels of storytelling in this process, all of which are still widespread:

There’s the narrative a game has in the first place. You’re there to rescue the princess, you’re there to slay the princess, whatever. As a viewer, you might have the added narrative layer of the player learning about or reacting to the story, but the root story is the one the game is designed to tell.

Then there are stories invented by the players that still operate under the game’s world and logic.

Then there’s the full abandonment of the game mechanic aside from as stage. Garry’s Mod can be used to make games and is designed to open up this end of the spectrum, and Source Filmmaker completely departs from the game premise – Skibidi Toilet takes place far on this end of the spectrum, maybe even off of it.

Skibidi Toilet remembers its heritage in video games – video game characters and models, the first-person camera angles, the fact that they’re literally shot from a person’s head perspective, guns and weapons in arms akimbo at the side of the screen, enemies bearing down on the POV – these are all familiar video game features. Later, there are HUD overlays. It does not occur to you at first to wonder why you’re seeing it this way.

But Skibidi Toilet has a lot up its titanic sleeves.

The first smoldering clue that this series has something really interesting going on, over the first dozen or so episodes – which is to say, the first few minutes – is the dawning realization that the camera is always diagetic. Every single shot has a camerahead behind it, filming.

With this realization, some of the more inexplicable elements suddenly make sense. The toilets are always lunging straight for the camera because he is an enemy.

Do you need arms to have an arms race?

It’s possible you’re wondering: okay, so that’s the basic plot, but what is Skibidi Toilet, like, about? Does it have themes?

I’m so glad you asked. Skibidi Toilet is about technological escalation during warfare.

The nature of the conflict changes dramatically over the course of the series. Skibidi Toilet is breathtakingly internally consistent about who has what capacity and when.

For instance, perhaps the first technology we see change hands is size. From very early on (even in the first few otherwise dubiously-relevant episodes), we see that there are small toilets and large toilets. There are a few plattoons of regular-sized toilets led by one very big toilet, maybe up to many stories high.

And yet, all of the AV Army we see at first are about human-sized. When the first large camerahead appears, it’s maybe twice as tall as a human, kind of a buff Bigfoot creature. Strong, but not a game-changer. The introduction in Episode 18 of an actual many-stories-tall AV kaiju – pardon me, I’m being told by the loyal soldiers of the Skibidi Toilet Wiki that they’re called “titans” – deeply transforms the battle. By the very next episode, we see cameraheads relaxing while the titan does its work fighting, and into the future, cameraheads seem to go from constantly afraid to living more of a relaxed lifestyle on the winning side. Titans remain a crucial tactic for the rest of the series.

The titans also become the first of a trend of recurring characters, which I suppose makes sense – a few titans are presumably substantial investments. (Obviously, we never get any idea where or how new technologies are invented, or how any of these soldiers are born or created, or where resources come from. It’s not ratfic, it’s Skibidi Toilet. Relax.)

Not all advancements are especially useful. We first see a camera on gangly metal crab-legs in Episode 12, alongside an advancing camera army. It’s a few episodes later when we see toilets on crab legs. The advantage of this is unclear – the toilets already move, and maybe that’s why this doesn’t confer a strong advantage. We see some toilets on crab legs afterwards (maybe they’re going a little faster?), but they’re not uniformly better.

As goes war. Unpowered military gliders offer some unique advantages, like fuel efficiency, deploying troops together rather than dispersed as if landing by parachutes, and being unconstrained by certain aircraft treaties, and multiple countries developed them in World War II. But gliders are not an important part of any military strategy today – they’re just not as good as planes and parachutes and so forth. We tried them out, we went back – the technology is still around, it’s just not optimal. That’s what I see the situation with the crab legs to be.

Far more impactful is the mind-control-parasite strategy. I think this might have been inspired by the AV army’s use of a camera with a toilet base in Episode 16, but it’s the Skibidi Toilets that pioneer the technology: infiltrating a large AV warrior by using a smaller-than-life toilet, living inside the host’s body. (Helpfully indicated to the viewer with crackling lines of electricity around the head of the infected.) The AV Army later develops a crude variation, in which human-sized cameraheads hijack a toilet Titan, but it’s not quite the same. The hijacking of powerful AV titans remains a useful Toilet strategy for the rest of the series.

The AV Army, in response, looks for solutions elsewhere – they invent sound weapons that play the THX riff, disabling both regular toilets and parasitic toilets inside hosts. They also produce a TV-headed woman who teleports, introducing who I believe is the first of the non-titan recurring characters. Interestingly, I think only her or maybe a very small number of other AV warriors can teleport – admittedly breaking the “technological development” pattern, because you would think that if she could do it, others could be taught the skill. They’re all mechanical, right?

This is actually kind of confirmed in the universe – we see AV people both large and small being “repaired” with mechanical tools rather than bandaged by doctors. So maybe there’s some story there, or maybe not. I don’t know. I didn’t check.

Either way, the progression is tightly adhered to, and this is only a tiny smattering of the developments. Weapons and strategies and body forms of both sides expand and diversify over the series. The Toilets even produce some true body horror combatants with the body of a camerahead and the head of a Skibidi Toilet, if you can even imagine such a thing.

At one point, an AV warrior’s arm is ripped off on the battlefield. It detaches an arm from a nearby dead toilet construct and just attaches it onto itself, where it starts working right away. Insofar as Skibidi Toilet has worldbuilding, I think this moment is crucial – it shows the depths to which these two seemingly disparate species are innately interoperable, and goes a long way to explaining the rapid pace of the (to to speak) arms race throughout the series.

This rapid technological exchange has the obvious Doylistic interpretation: it’s more exciting to show people something they haven’t seen before, and the creator gets new ideas the longer the series runs. Also, the entire series is built on “blending components of 3D models together” – see human-toilets, human-cameras. But the attention to detail and consistency? That has to be intentional. Watsonianly, this is a story of two powerful biomechanical species in a technological arms race.

There are a few weapons that emerge later that don’t feel like they follow this pattern, except for in a metatextual way. As the series matures, its aesthetics mature too. I think the artistic high point of this is when we see an AV army champion, facing a toilet squadron, wield a pair of plungers like swords. As far as I recall, we never saw any plungers before this, but it feels, instinctively, like an older and more disciplined form of warfare. We know in our bones that this plunger camera is cool. A real smooth operator.

But down the line, there are just knives. Before this, we saw toilets die to two things: flushing the head, and sort of generically in explosions. But by episode 50 or so, an AV Army guy just stabs a toilet in the head, with a knife. There’s blood (albeit in a 2012-video-game particle-effect-cloud kind of way). In addition to the space-age ray guns or directed sound weapons, realistic guns enter play around this time.

The psychological effect of this is jarring. You are reminded that DaFuq!?Boom! is not under the thumb of any major American television network. I think it’s an interesting artistic choice, but I’m still not sure what to make of it.

Oh, and other hallmarks of war are all over the series. In Episode 21, two cameraheads apparently interrogate a captured toilet in a dark room regarding the location (or… something) about a particular recurring Toilet Titan (this one has the head of the G-man from Half Life. He is called the G-Toilet, according to the Skibidi Toilet Wiki. I mostly didn’t refer to outside information, since I think personal interpretation is part of the fun of such a surreal piece of art, but a friend pointed out that the model is recognizable if you’ve played Half Life, which I haven’t, and I reluctantly admit that “G-Toilet” is a better name than the one I’d come up with, which was “Titan Toilet Richard Nixon.”) Anyway, that’s fucked up, right?

And we watch as the cameramen, in their new hegemony, hound and beat single toilets (who they now outnumber.) They patrol the streets but in a relaxed, this-is-just-my-day-job way. They sit on the empty husks of defeated enemy toilets.

Even in the later episodes, when the apparent primary drivers of the action are huge familiar titans, Skibidi Toilet never quite forgets the little guy. After one brutal toilet attack, the POV camerahead is injured and we see its vision black out… but reawaken, moments later, in an AV hospital ward. There are medical personnel and cameraheads in wheelchairs. We’ve seen titans being repaired but we’ve never seen regular cameraheads being repaired. This too reinforces that the tide is turning in the AV Army’s favor – that it’s now possible to give care and repair to the previously-disposable footsoldiers.

(Does being on the winning side of a war mean regaining your ability to exercise your humanity? Discuss.)

I think my favorite episode is 58, after the toilets have taken the lead.

It features a late-stage-Skibidi Toilet-typical battle involving both smaller combatants and titans. who look cool, and do cool stunts. At the start of the episode, large bladed toilet drives by with a camerahead impaled on one of its sword-arms. (At first, this seems unreasonably cruel, but remember we’ve also seen the AV Army sitting on the husks of dead toilets – is this really any different?)

Anyway, the episode refers back to – almost centering – these three little identical regular cameraheads, clinging to a streetlamp amid the chaos. We’ll never get to know them as individuals. We’ll never even know if we’ve seen them again after this episode. But we are given space to care about their survival and personhood for just a moment.

Wait, maybe you don’t want to watch this

The series does drag. I don’t want to overstate it. The realism is superficial; we have no idea where either of these groups come from, or why they’re fighting. We don’t know how they produce new soldiers, or where they’re fighting, or why they can’t just build one titan the size of the city and be done with it. Often a previously unseen enemy titan will emerge from somewhere at a dire moment and it’s unclear where it came from or how the latest skyscraper-sized Titan Toilet could have remained unnoticed until right now. Doesn’t the AV Army have literal sentient security cameras? How did you miss that, Harold?

We have indications that both sides have culture and internal lives, but we don’t know anything about those. Without a good explanation like “toilet mind control parasites momentarily creating turncoats”, literally every toilet is fighting literally every camerahead – the war is fixed, and the war is absolute.

This gets draining, especially combined with the short-format. See, Skibidi Toilet is highly responsive to the Youtube algorithm. Around the start of Skibidi Toilet, Youtube really liked Shorts (phone-screen-aspect videos under a minute long), and so dozens of episodes are that short. Many are under 30 seconds. The effect of that is that each 30 second episode has to have an entire and complete arc, and the arc usually ends in “a Skibidi Toilet throwing itself disorientingly at the camera.” They are always singing the same song.

I watched it for the first time in one two-hour sitting, and that was probably part of it. I have enough Gen Alpha joie de vivre that I can take a lot of 30-second absurd shorts, but… maybe not that many.

I can’t completely compare it to qntm’s proposed film concept “One Hour Fight Scene”, because Skibidi Toilet has more diversity of setting and arc than that, but the repetitiveness and even the constant escalation is just… grating.

So I’d advise not watching it all at once – but that’s bad advice too, because I discovered that the wordlessness and repetition lends it a dreamlike quality of transience. 24 hours after watching Skibidi Toilet, you’ll be like “what happened last time? Which titan just did what? Have we seen that character before or not?” I legitimately found that taking notes helped. Maybe there’s just no way to comfortably ride this wild steed.

For what it’s worth, Skibidi Toilet is mostly self-aware about its descent into formulaicness, and there are a lot of small moments playing with this that make the series sparkle. When the AV Army steals secret documents from some kind of Toilet research base, the documents… just write out the lyrics of the Skibidi Toilet song in bungled Cyrillic. The plot beat is just that familiar one of stealing big enemy plans. It doesn’t really matter what the plans are, and this deep in, you know this and I know this and DaFuq!?Boom! knows this.

At one point, we see a camerahead scientist “drink” a cup of coffee by dumping it down the front of its shirt.

And later on, a human man apparently representing DaFuq!?Boom! himself shows up in the series – a face we’ve previously only seen as a youtube avatar, suddenly breaking the assumed laws of the narrative by appearing in his own creation. I won’t spoil any more, but it’s a buck fucking wild ride.

I don’t want to assure you that it’s worth it. I don’t know you. I won’t say that. At the end of watching some small toilets fight some small camera guys, you’ll be rewarded with a much bigger toilet fighting a much bigger camera guy. Does that sound fun? Hey, if it does, I know a series you might like.

Found footage and horror

Skibidi Toilet is not really a horror series, but it takes a lot of its beats and inspiration from horror.

The oldest kind of internet-original video horror is screamers. It’s the cheapest and easiest way to make horror – take a pretty normal piece of footage or imagery, let people watch it for a few minutes, then BAM! Sudden cut to a creepy face. It’s the digital equivalent of yelling “BOO” behind someone’s back, automated for your inconvenience. Ghost Car [content warning: bro, read the room] is a classic of the genre, 19 years old and with 41 million views at the time of writing. The hook of early episodes of Skibidi Toilet is not much different from 19 years ago – some weird stuff happens and then a distorted face flies real quick at your screen.

DaFuq!?Boom! has stated that he was literally inspired by toilet-related nightmares, so the surreality and sense of panic at the outset make a lot of sense. But as the plot develops, Skibidi Toilet starts taking influence from a wider variety of genres, especially horror subgenres.

One of these is found footage. We’ve touched on the cameraheads and their diegetic filming already – we also see alterations to the footage, like a cameraman falls and the footage goes wavery for a second, or a camerahead is hit by a beam weapon and the footage distorts.

Horror that pretends (at some level) to be reality is not new – how many ghost stories are intentionally told as “no, my cousin’s friend’s friend said this really happened to her”? Dracula in 1897 and The Phantom of the Opera in 1910 are both framed as letters and diaries and news reports.

Skibidi Toilet is obviously not going full Blair Witch Project or War of the Worlds in terms of trying to convince us the story is real, but just in the footage, the full commitment to the bit that all of this is being witnessed by a person(-thing) really adds intrigue and serious sophistication. The shot will end when the POV camerahead either chooses to end the shot, or when it dies. It builds tension by default. I think there’s maybe one moment in the whole series when the filming camerahead dies mid-episode and we are swapped without context to another camerahead. Everything else flows.

How any of this footage gets to us, relatedly, is unclear. It’s not so found-footage as to say “here are the tapes I found in a box in the woods” or “we now present footage from the Joint War Archive, documenting our shared dark history prior to the Toilet-AV Peace Treaty of 2065.” (But that’s pretty good – hey, DaFuq!?Boom!, if you’re reading this, feel free to use that.) But I like to imagine that a peak virtue among AV society is the act of witnessing, and that having and curating this footage of dark moments is good to them. That might explain why so many of them wade into battle, why there’s always someone watching from a good spot, why so many of them stay under fire until the last moment.

There are also underground institutional labs that strike me as borrowed from horror – your Half Lifes, your Resident Evils, your Stranger Things, your SCP Foundations. (Given that Skibidi Toilet borrows other assets from Half Life, it’s kind of the obvious thing to go for.) We see surprisingly little combination between these laboratories and the technological arms race, although I think it’s implied that many new developments come out of these labs. These environments connect more to the post-apocalyptic elements of the series and the vestiges of humanity and the possible origin of the Skibidi Toilets and the AV Army both – although any real answers remain beyond me, if they exist at all.

The real culture war

I didn’t expect, before starting the series, that the eponymous Skibidi Toilets would be the villains. But the existence and narrative role of the AV Army opens up a very interesting series of questions.

What fraction of the viewers of Skibidi Toilet have ever worked with a TV camera? Or a regular camera, for that matter? Wouldn’t they just do all of that on a phone?

I notice that the AV Army doesn’t have any smartphone-heads – or laptop-heads, for that matter. Even flatscreen-heads are rather thin on the ground. They use an older aesthetic: steely surveillance cameras, CRT televisions, tape video recorders or film cameras. They wear suits. Their theme song – only heard a few times, possibly because of Youtube copyright strikes, but distinct – is an echoey version of 80s hit Everybody Wants to Rule the World.

Their enemies are, of course, the toilets: frightening, gross, offensive, always lunging at the viewer, always singing their song that has certainly become repetitive by the 20th time (and you will not escape Skibidi Toilet having heard the Skibidi Toilet song only 20 times.)

Even Source Filmmaker is a millennial’s animation tool. DaFuq!?Boom! isn’t a babe in arms, he has years of machinima experience.

People drag Skibidi Toilet as trash, as brainrot, as the meaningless poison of the youth du jour. Do they see the war? The uncouth screaming toilets versus the cool suits of the older generation? I have no idea how intentional this was, but it just sits with me.

A friend, who is much closer to the usual Skibidi Toilet viewing age than I am, described that the cameraheads evoked a sense of omnipresent surveillance that rang true to his life. I suppose it’s true of all of us, even if the older generations are less aware of it. Everybody has a camera on them at all times. Everybody has a screen on them at all times. The AV Army may be our heroes but they’re also literally a surveillance state. We watch through the eyes of the smallest and weakest among them as they die repeatedly.

I don’t know. I just think it’s an interesting angle on the show, intentional or not.

A glorious collage

DaFuq!?Boom!’s earlier Youtube work includes other popular machinima skits and series, as well as SFX masterpieces like “Optimus Prime Crushed in Hydraulic Press” and “Optimus Prime Explodes in Microwave”. He’s clearly a talented 3D animator.

There’s one predecessor series, the DaFuq series, which feels to me like the real precursor for Skibidi Toilet. This series involves clips of regular scenes – people shopping, walking in a park, etc – until every model suddenly distorts, and there are screams as they’re rearranged into a surreal hybrid tableau.

This feels like the invocation of a thing that I’m sure machinima artists have done since the beginning – just played with the models, used them as toys, as sandboxes, made monstrosities just for the hell of it while learning the tools. DaFuq!?Boom! renders these dollhouse abominations as growing from realistic scenes, thus turning them into surreal horror-comedy. I am absolutely certain this is what Skibidi Toilet grew out of.

There’s a genre of media on the internet where the creator clearly didn’t intend for a goofy new project to grow into an epic, but it did. Griffin Mcelroy recorded The Adventure Zone, a game of Dungeons and Dragons with his brothers and father, as a podcast, which they had intended as an easy interlude to their regular podcast while one family member was on paternity leave. But instead the game spiraled out for months, developing real characterization, narratives, a universe-bending arc, and it became a beloved franchise now adapted as a comic book. He described the unexpected whirlwind as “a car that learned to fly.”

Now, I’m sure that novelists have been starting what they think is going to be a short story and what spirals into, I don’t know, Moby Dick, or The Bible, since the beginning of time. But crucially, in novels, once you figure out it’s going to be a big deal, you can go back and rewrite the beginning to fit with the quality and scope of your vision.

But barely-planned epic serial media, which the internet is rife with, doesn’t let you do that. The beginning is already out there.

This means:

A) If the authors improve over time, the beginning will still be rough. You can watch Skibidi Toilet grow. Literally: in episode duration and in physical size (it started as a series of youtube shorts and thus the first few dozen episodes are in the upright-phone-screen aspect ratio, but past episode 38 all videos are full-screen.) Figuratively: in animation and visual quality, in coherence, there’s a plot, there’s characters, etc.

B) Relatedly, the authors are stuck with whatever stupid gags they started out with. They’re stuck with wizards named Taco, with teenagers obsessed with Nicholas Cage, with Minecraft nations named “L’manberg” because they didn’t have any women and they wanted to sound European, with toilets with human heads sticking out of the bowls that you can kill by flushing them.

And it is so, so beautiful. To wax philosophic for a moment, I don’t think you’ve truly appreciated art until you’ve been swayed to your very soul by the inner turmoil of Taako the Wizard or the sad little pixels of a Minecraft face or the fact that the Nicholas Cage teen stopped liking Nicholas Cage or the camera-headed guys giving each other thumbs-up after flushing toilet-men – by something so dumb it’s embarrassing. Yes, it’s stupid. It’s so very, very stupid. A novice home-cooked meal or an inadvisable crush or an inside joke can also be stupid. They can also be everything.

Past the veil of shame is where the dark, gross, raw workings of the heart lie. Meet me there.

Anyway, another interesting thing about Skibidi Toilet is that almost all of its assets are recycled from elsewhere.

Take the AV army. All of the models are other people’s – suited figures and AV equipment. DaFuq!?Boom! cites the creators in his video description. TVheads are a surprisingly common modern internet chimera. They’re not especially common characters in any particular piece of media, but look it up and you’ll find people cosplaying and making art of TVheads. They might have stemmed from people inspired by the 2000 character Canti, a robot with a TV-like screen for a head in the anime FLCL. But the modern suited TVhead is now a fully separate species of cryptid. Yoink!

Probably the earliest camera-headed character appeared in a series of frankly awesome 2007 Japanese PSAs against movie theater piracy, in which dancing, suited, camera-headed people(?) dance and illegally film movies. Oops! Culture has been changed forever!

Interestingly, the diagetic camerahead – a human with supernatural camera head or features who films relevant parts of the series – also plays a minor but impressive role in a legendary 2010-2019 slenderman youtube series and alternate reality game. In EverymanHYBRID, the supernatural villain character (uh, the one who’s not slenderman), the one who’s been hijacking the main team’s youtube channel, also begins hijacking human victims and using them as living video cameras. We never see a camerahead in EverymanHYBRID – it’s a live-action series on a shoestring budget that plays hard for realism – but we do see their camerawork, and we see the main cast react with horror to the thing shooting the picture. It directly asks the question “who’s behind the camera” with a horror flavor, which is of great thematic interest in EverymanHYBRID and which I was surprised to see echoed in Skibidi Toilet.

(I have no reason to think DaFuq!?Boom! has watched EverymanHYBRID, but it’s a very interesting parallel.)

In the first version of this review, I wrote that speakerheads don’t have much in the way of cultural context, but how could I forget Sirenhead? This creepy monster invented by artist Trevor Henderson is a slenderman-esque figure with multiple gaping fleshy megaphone heads, that like the cameraheads, was appropriated by the internet as a folk villain.

Skibidi Toilet’s speakerheads are the domesticated version – they’re just suited humanoids with speaker clusters for heads, in and among the TV heads and cameraheads. The speakerhead titans in Skibidi Toilet are major characters, apparently developing out of the AV Army’s experiments with sound-based energy weapons.

These more human speakerheads, and the idea of cameraheads and TVheads and speakerheads all forming a natural alliance based on shared structure? I think that’s all pure innovation on DaFuq!?Boom!’s part.

Even the Skibidi Toilet song is yoinked! It’s a remix by tiktokker doombreaker03, of the songs “Dom Dom Yes Yes” by Biser King and “Give It To Me” by Timbaland.

(By the way, Biser King is Bulgarian and Timbaland is American, and the remixed song appears to have become viral in Turkey before being used as a video soundtrack by American Tiktokker, Paryss Bryanne, which in turn inspired Skibidi Toilet creator DaFuq!?Boom!, who is Georgian (as in country of Georgia) – thus making an unusual international journey even before reaching the world’s ears as THE Skibidi Toilet song.)

My early interest in tech and tech culture came out of the open source movement, and I have an admittedly rosy-eyed optimism around things like creative commons and free cultural exchange. The machinima community follows this spirit 100%: adapt what you want, build something new, share it around. While I’d never thought about it before, Tiktok culture loves to do this. And Skibidi Toilet rejoices in it too – it is an exquisite collage of borrowed characters, models, songs, and effects all repurposed in creative new ways. It’s a hit kid’s show that’s absolutely unbeholden to any studio or copyright law or content standard other than the bare minimum enforced by youtube. It’s a car that learned to fly. And it’s glorious, and it’s clever, and most importantly, it’s an absolute trip.

The late game

I will say that over time, along with more beautiful atmospheric animations and longer episode lengths, the series Marvelfies. It’s easy to see why – from very early on, it was about escalating fights and drama. So why not scale it to its extreme: huge clashes between titans, dramatic soundtracks and panning action shots. Get some revelations and some shadowy underground bosses and some generic one-liners in there too. Why not?

I personally draw the line at the one-liners – it’s so surprising to hear speech in Skibidi Toilet that I feel it should be conserved or avoided entirely. But as of the most recent episodes, the plot is so convoluted that it’s now necessary to verbally explain a bare minimum of what’s going on.

(…Okay, when I say it like that, that’s actually a really high bar that basically no other story meets. Fair enough, Mr. Boom.)

And the series loses some creativity on the way, I think – not all of it, but it has clearly turned from a post-apocalyptic psychological horror franchise with war elements into an action franchise, and I preferred the genre mixing pot.

One notable plot point that I have mixed feelings about (and if this is partially due to the fact that I was four drinks in at this point when I first saw it and completely missed what was going on, it’s surely impossible to know) – is that a force of alien Space Toilets arrive. They have their own space-age technology and aesthetics – red lights, drone-like hover capacity, fancy shields, the works. At first, they seem to be allied with the Skibidi Toilets, as one might expect; however, the alliance fractures. As of now, the Skibidi Toilets have now teamed up with the AV Army against the powerful alien forces.

And, like, I guess? It’s very Watchmen. It feels like aw, okay, sure, now you have fans of both sides and lines of action figures sold at Target, they have to team up as heroes against a convenient new enemy. Sure. Yes, obviously I bought one.

I’d be more invested in the team-up plotline if we saw either more or less of whatever humanity the Skibidi Toilets have – while we’ve seen lots of humanizing interactions between AV Army members, even the rudiments of Skibidi Civilization are mysterious to us. On the other hand, being forced to cooperate with a nightmarish creepypasta jumpscare entity that has at most a semblance of relatability would be very interesting too. Either way, we have, alas, seen very little of the timbre of the AV Army-Toilet alliance.

More interesting is the side plot in which human beings have appeared – survivors, apparently, people who have been holed up since the fall of their world, their presence further suggesting that the entire series has taken place on some post-catastrophe Earth. They’re with the alliance too, and they’re weak and underpowered in this new paradigm.

Mostly the series has drifted away from surreal comedy-horror and into solely epic action scenes, with occasional difficult-to-parse intrigue. A return to form would not be amiss. But it still has a lot of heart in it, a frankly wild amount of implicit worldbuilding, and as a visual spectacle it’s only growing over time. I, personally, am curious to see if the AV-Toilet alliance holds, and if the human survivors will find any place in the world to come.

I hope we all find a place in the world to come.

Final rating

5/10. I have no idea how this was monetized and I hope the creator makes ten million dollars off it. If you’re going to watch the whole thing at once, I recommend being drunk.

This review was written as an entry for Astral Codex Ten‘s 2025 “Anything-But-A-Book Review” contest – it didn’t make the finalists, but watch for those on ACX in the coming days.

Thank you Nova for suggesting the title of this post.

Support Eukaryote Writes Blog on Patreon. Sign up for emails for new posts in the blog sidebar.

Crossposted to: [EukaryoteWritesBlog.com – Substack]